HOW TO MAINTAIN ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION DURING COVID-19? EXPERIENCES FROM ARMENIA, GEORGIA, AND UZBEKISTAN

Author: Eka Paatashvili

Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand COVID-19’s full impact on routine immunization, we must look at how countries have modified routine immunization service delivery and financing and trends in vaccine coverage. We must then consider future systemic improvements to further strengthen immunization programs and increase their resiliency in the face of future shocks to the system.

The experiences of Armenia, Georgia, and Uzbekistan provide an opportunity to understand the key challenges that countries in the European region have encountered with maintaining routine immunization during the COVID-19 pandemic and the strategies they implemented to address these challenges. Here are some of the key takeaways.

RESTORING AND MAINTAINING ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES

In all three countries, it was challenging to maintain essential health services, including immunization, while mitigating the impact of the pandemic. While immunization services were never stopped or paused in any of these countries, they did experience reductions in coverage and delays in vaccination at some point during 2020.

- In Armenia, compared with 2019, the 1-year-old target group coverage dropped by 0.2%, the 2-year-old target group dropped by 2%, and the 6-year-old target group dropped by 1.5%. The key challenge to timely vaccination, which has dropped by 60%, was due to the war and the fear of getting COVID-19 when visiting clinics.

- Uzbekistan mostly maintained its 97-98% national vaccination coverage rate, with immunization coverage dropping 1.5-2% lower during the summer crisis.

- Georgia experienced a drop of 7-8% in its national immunization coverage. There was 5-6% decrease for Hexa-1 and Hexa-3 vaccines among children under 1-year of age, however, a higher decrease was observed for booster doses. For the newly introduced HPV vaccine, coverage reached only 23% in 2020.

March and April 2020 made up the most difficult period of the pandemic for these countries. The lack of PPE, restricted public transportation, as well as general fear and uncertainty around COVID-19 among the general population and health care workers, resulted in reduced utilization of vaccination services. And yet, none of these countries experienced a VPD outbreak.

The efforts of the EPI and health program providers, including tailored catch-up strategies and supportive supervision activities, helped the countries restore vaccine coverage rates, overcoming the reductions in coverage that occurred during the initial stage of the pandemic.

- Armenia used daily monitoring of routine vaccination countrywide, which helped to quickly identify the current vaccination dynamics and respond to bottlenecks.

- Georgia focused on the micro-planning approach, where public health authorities supported primary health care (PHC) clinics in identifying and dealing with individual missed opportunities for vaccination. In addition, to ensure better access to the immunization services and flexibility for families that had moved to rural areas, children could receive vaccination regardless of their place of residence.

- Uzbekistan actively operated mobile outreach groups for the regions under transportation restrictions. This approach enabled them to gather beneficiaries at medical facilities and schools for their routine vaccinations. When needed, mobile groups also used home visits to deliver immunization services.

PUTTING SAFETY FIRST

To adapt to the increased safety risks and lockdown strategies, the countries followed WHO’s recommendations during the development and introduction of national guidelines, along with assessment checklists, to help safely maintain immunization services. In addition to setting updated sanitary-epidemiological norms, the new regulations defined specific vaccination hours to separate patient flow. The regulations, applied to both public and private sectors, were initially found to be difficult to follow by service providers. To help ease the transition to these new protocols, public health authorities provided trainings, supportive materials, and regular monitoring meetings face-to-face as well as online. To reduce the risk of infections, Georgia implemented a new system with online appointments and remote counseling by phone.

Due to safety concerns, the National CDCs of Armenia and Georgia avoided large-scale catch-up campaigns during World Immunization Week in April 2020. In contrast, Uzbekistan followed WHO’s recommendations on distance, sanitization, and PPE requirements to safely conduct immunization campaigns for the HPV second-dose vaccination in March and large MMR catch-up campaigns in June. Both vaccination campaigns in Uzbekistan reached 97-98% coverage.

PRIORITIZING ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION FINANCING

Historical prioritization of immunization was a key factor in securing immunization funding in the region. Despite the financial hardships imposed by COVID-19, Georgia and Uzbekistan have so far been able to secure their full routine immunization program budgets. Due to the war, Armenia had to cut all health care program budgets, including the immunization program which experienced its first reduction in 16 years. However, Armenia did not believe there was an effect on immunization program activities.

Armenia and Georgia kept Gavi post-transition funds for routine immunization catch-up activities rather than taking advantage of the opportunity to redirect them to COVID-19 needs. Uzbekistan did reprogram Gavi funds to procure sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), however this seems to have had no impact on routine immunization.

OVERCOMING VACCINE PROCUREMENT AND SUPPLY CONSTRAINTS

Due to international travel restrictions and local transportation bans, the countries were anticipating delays in vaccine shipment and delivery. At the beginning of the pandemic, Armenia did experience stock issues, including a national stock-out of hep-A and meningococcus vaccines and a late shipment of flu vaccines from UNICEF. Similarly, Uzbekistan had to delay HPV vaccination. While Georgia did not experience any interruption in the procurement and supply of routine vaccines, there were other barriers with commercial vaccines like hep-A, meningococcus, and chickenpox vaccines that had to be addressed. The countries have since been able to resolve these acute supply constraints.

SHARING AND SHIFTING RESPONSIBILITIES DUE TO OVERBURDENED HEALTH WORKFORCE

Since the start of the pandemic, the country EPI teams have been involved in COVID-19 response activities and, more recently, COVID-19 vaccination preparedness and implementation became their direct responsibility. This has placed additional responsibilities on already overburdened EPI personnel.

Later, the increased workload and spread of infection among frontline medical workers and epidemiologists became a serious concern impacting immunization service provision. Uzbekistan suffered a significant loss of health worker capacity during a summer outbreak, requiring the Ministry of Health to engage other doctors, specialists, and public health workers in the provision of PHC and immunization services.

WITHSTANDING VACCINE HESITANCY AND DEMAND HURDLES

As social media in Armenia and Georgia showed significant resistance to COVID-19 vaccines, both countries anticipated an increase in hesitancy for routine immunization. In Georgia, a knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) survey revealed low, but growing, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance – from 33% in August to 46% in November 2020. Fortunately, this hesitancy to COVID-19 vaccines did not transfer to hesitancy for routine immunization, and demand for routine vaccines resumed as restrictions began to ease. In Uzbekistan, hesitancy was not a concern for the COVID-19 or routine vaccines.

In summary, while the dynamics of the pandemic differed across Armenia, Georgia, and Uzbekistan, all three countries have largely been able to maintain their routine immunization programs by focusing on safety, maintaining financing, overcoming supply constraints, shoring up the health workforce, supportive supervision and performing targeted catch-up campaigns when needed. As countries around the world implement COVID-19 vaccines, they may face new challenges and opportunities with maintaining routine immunization services. There is a need to stay focused on core functions and activities such as those highlighted in Armenia, Georgia, and Uzbekistan, while exploring opportunities for service delivery improvements and innovation. For example, countries can explore how technologies can replace education and outreach visits and face-to-face communication with parents. Countries will also be eager to understand how PHC services can effectively integrate massive COVID-19 vaccination of their adult populations without disrupting childhood vaccinations. LNCT hopes to provide further opportunities for countries to learn from each other’s experiences with maintaining routine immunization during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The blog was initially published on the LNCT platform.

Latest News

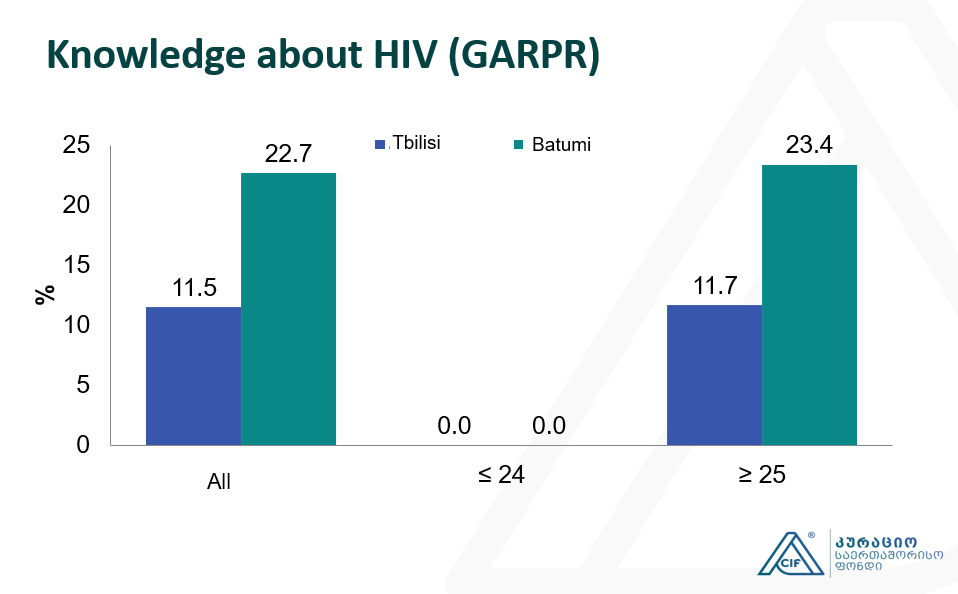

Integrated Bio-behavioral surveillance and population size estimation survey among Female Sex Workers in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia, in 2024

We’re excited to announce the completion of a significant study conducted in 2024 that estimates HIV-related risk behaviors and HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers (FSWs) in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia. Building on surveys initiated in 2002, the…

Curatio International Foundation at Eighth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2024)

During 18-22 November 2024 in Nagasaki, Japan will be hosting the Eighth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research. Curatio International Foundation will actively participate in the symposium, presenting research outcomes and acting as panelists on the different sessions. Read more…

“The Informatics and Data Science for Public Health: Sustainment Plan for Skilled Labor Force Development”

Curatio International Foundation publishes the report “The Informatics and Data Science for Public Health: Sustainment Plan for Skilled Labor Force Development”. The report highlights the assessment results conducted in Georgia, Kazakhstan and Moldova, with the aim to evaluate market, supply…

Janina Stauke from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine shares her internship experience

Janina Stauke from LSHTM was a CIF Intern during the 2024 Summer internship program, where she contributed to a project focused on understanding why individuals experience impoverishment due to health spending. In her role, conducted comprehensive literature review and has…

Jolly Mae Catalan fromUniversité Libre de Bruxelles shares her internship experience

Jolly Mae Catalan was a CIF Intern during the 2024 Summer internship program, where she contributed to a project focused on understanding why individuals experience impoverishment due to health spending. In her role, Jolly examined the impact of the accessibility and…

Georgia’s Journey to Integrating Rehabilitation Services into the Health System: Insights and Lessons

This Learning Brief captures Georgia’s journey in integrating rehabilitation services into its health system, offering a detailed account of the strategies, actions, and lessons learned from this transformation. Supported by USAID, Accelerator and Curatio International Foundation, the project aimed to…

Report on Rehabilitation Data Flow in Georgia’s Health Information System

The Curatio International Foundation (CIF) publishes report on Rehabilitation Data Flow in Georgia’s Health Information System (HIS). This study investigates how rehabilitation information currently flows within Georgia’s HIS, identifies strengths and shortcomings, and provides recommendations for enhancing the rehabilitation information…

Georgia: a primary health care case study in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

The case study examines primary health care (PHC) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Georgia between January 2020 and July 2021. The Astana PHC components are used to consider integrated integrated primary care and essential public health functions,…

Adult vaccination in Asia and the Pacific

Curatio International Foundation in partnership with Asian Development Bank publishes a report entitled “Adult vaccination in Asia and the Pacific- policies, financial needs, and fiscal impacts” Immunization is one of the most cost-effective tools for improving health and well-being. The coronavirus…

Assessment of the Quality of Maternal and Neonatal Services in Montenegro

Curatio International Foundation (CIF) publishes a report on the Assessment of the Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Montenegro, a project supported by UNICEF and in collaboration with the Montenegro’s Ministry of Health. This initiative enriched by CIF’s expertise,…

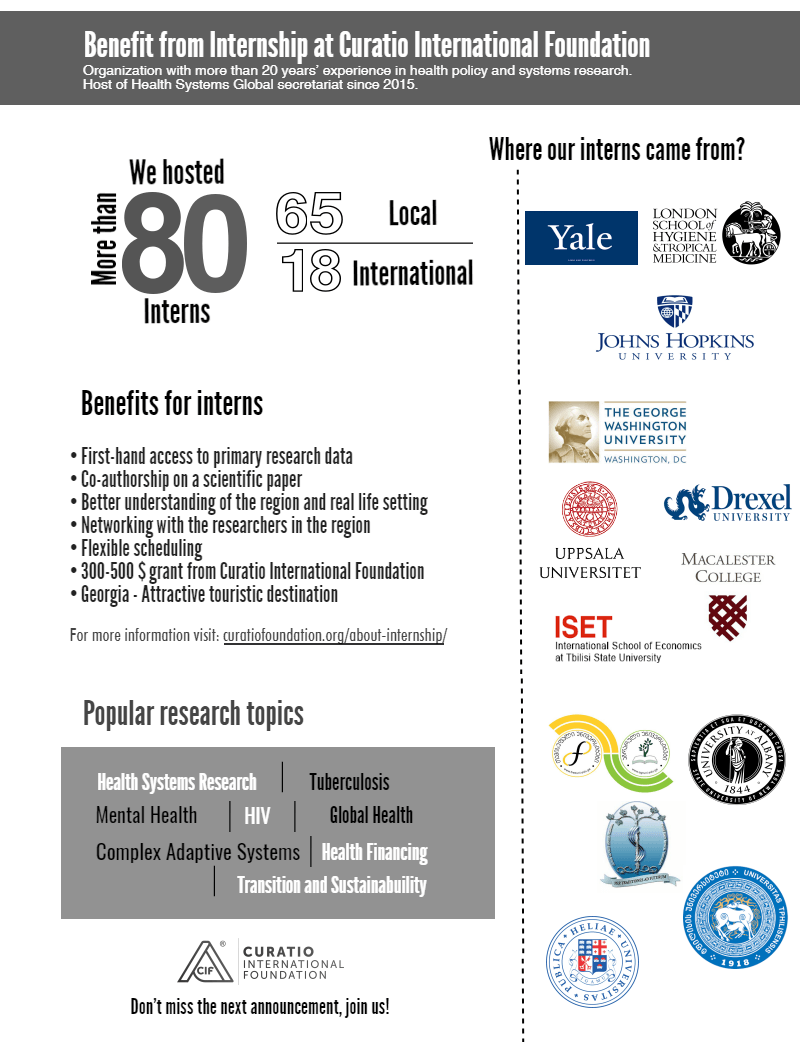

Call for Internship 2024

About host organization Curatio International Foundation (CIF) is a not-for-profit, non-governmental organization with a mission to improve health through health policy and systems strengthening. CIF’s work is underpinned by three core values: hearing needs; building on local strengths; and delivering…

Georgian state rehabilitation program: implementation research study report

The Curatio International Foundation (CIF) publishes implementation research study report, which aims to document the initial results and challenges of Georgia’s state rehabilitation program, to inform and facilitate the program’s timely scale-up beyond the initial package of interventions. This study was conducted by…

NEW Barometer, study focusing on the pharmaceutical sector

The Curatio International Foundation publishes a new Barometer, a study is focusing on the pharmaceutical sector. The purpose of the study is to examine the inflation on healthcare with a focus on pharmaceuticals. The study includes the data of the…

Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia

The Curatio International Foundation, in collaboration with R4D (Results for Development) and USAID’s ‘Health Systems Strengthening Accelerator,’ conducted a stakeholder meeting on September 15th as part of the ‘Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia’ project. During the…

Linked’s workshop on HPV vaccine introduction and scale up, held on July 11-12th, 2023

In a significant step towards combating the impact of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections, in partnership with R4D, CIF organized a two-day in-person workshop in Istanbul, Turkey, to address the challenges faced by Middle-Income Countries (MICs) in HPV vaccine introduction and…

Training program focusing on interdisciplinary evaluation of rehabilitation interventions and patient outcomes

The Curatio International Foundation conducted a training program focusing on interdisciplinary evaluation of rehabilitation interventions and patient outcomes. This initiative was carried out as a part of the “Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia” project, in collaboration with…

Unlocking Success Through Learning: Workshop on Strengthening HR Capacity and Performance Management in Immunization

Multiple factors affect health worker performance and, by extension, immunization program performance. But what are the most important factors that lead to health workers performing well? During 6-7 June, about 30 participants, including government representatives and country partners from Armenia,…

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence and fostering civic engagement

Curatio International Foundation (CIF) is running the project entitled “Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence and fostering civic engagement” in partnership with Social Equation Hub (SEH). In the frame of the program on June 22 –…

CIF and the Results for Development / Accelerator combined their expertise to co-author an insightful blog, shedding light on Georgia’s commendable efforts to overcome limited data challenges and develop evidence-based policies for financing rehabilitation services

The Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labor, Health, and Social Affairs in Georgia has taken a significant step in extending financial protection for rehabilitation services through the Universal Health Coverage Program. With support from the Health…

Culminating event – Building Institutional Capacity for Health Policy and Systems Research and Delivery science (BIRD) in six WHO Regions

3-day culminating event was conducted in Beirut, Lebanon in the frame of “Building Institutional Capacity for Health Policy and Systems Research and Delivery science (BIRD) in six WHO Regions” program. The meeting aimed to reflect on achievements and learnings and…

Report on Phased (Stepwise) Plan for the Capability Development of the Priority Rehabilitation Services

The Inclusive Development Hub of USAID’s Bureau for Development, Democracy, and Innovation has partnered with the Accelerator to support countries in strengthening and integrating rehabilitation services in the health systems. Georgia was selected as one of the priority countries for…

Report on prioritization of rehabilitation services in Georgia

The Inclusive Development Hub of USAID’s Bureau for Development, Democracy, and Innovation has partnered with the Accelerator to support countries in strengthening and integrating rehabilitation services in the health systems. Georgia was selected as one of the priority countries for…

Report on Rehabilitation Service Costing and Budgeting

The Inclusive Development Hub of USAID’s Bureau for Development, Democracy, and Innovation has partnered with the Accelerator to support countries in strengthening and integrating rehabilitation services in the health systems. Georgia was selected as one of the priority countries for…

Mental health of young people during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken its toll on the mental health and wellbeing of the population globally. Even two years after the COVID-19 Pandemic breakout, the impact on the mental health of populations globally, particularly children and young people, is…

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence

Duration From: September 2022 To March 2024 Introduction and Overview The research project aims to promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence and fostering civil engagement. The project will achieve the aim through two objectives: Investigate the…

Mandatory Vaccination and Green Passes – Review of International Experience

Globally, the COVID-19 vaccination started at the end of 2020 and continues at a different paces in various countries. As of December 7 2021, 8 billion doses of vaccine have been administered worldwide, and 45% of the world’s population has…

Sustaining Public Health Gains after Donor Transition: What can we learn about Georgia?

The CIF research team publishes Synthesis Report entitled: “Sustaining Public Health Gains after Donor Transition: What can we learn about Georgia?”. The research project aimed to comprehensively evaluate donor transitions that took place in Georgia in the immunization program (NIP) after introducing…

Curatio International Foundation at Seventh Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2022)

During October 31 – November 04, 2022, Bogota, Colombia hosted the Seventh Global Symposium on Health Systems Research. Research team of Curatio International Foundation actively participated in the symposium, organized couple satellite sessions and presented research outcomes to…

Curatio International Foundation at Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

EECA HIV Sustainability Summit 2022 in Tbilisi

On September 26 – 28, EECA HIV Sustainability Summit 2022 took place in Tbilisi, Georgia, which aimed to mobilize national, regional, and international stakeholders and create a platform for the high-level dialogue on strategic vision and priority actions required to…

Study report: Adaptations made in TB response during Covid-19 pandemic in Georgia

The CIF research team publishes study report entitled “What adaptations were made in TB response during Covid-19 pandemic in Georgia: health systems perspective on the implications for TB case detection and treatment provision”. The research project aimed to study how the state…

New review of our recent study on Immunization in Kazakhstan

„The report offers the most clear, comprehensive layout of the problems of planning and providing immunization in the Republic of Kazakhstan and offers detailed solutions. In essence, the document is a step-by-step guide to fixing the situation and must be read…

New case study: Sustaining effective coverage with Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) in Georgia in the context of transition from external assistance

The CIF research team publishes new case study entitled “Sustaining effective coverage with Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) in Georgia in the context of transition from external assistance”. The study aims to better understand how and why Georgia was able to…

New case study: National Immunisation Program Transition from external assistance

The CIF research team publishes a new case study entitled “National Immunization Program (NIP) Transition from external assistance – Case Study from Georgia”. The purpose of this case study is to understand the transition of the National Immunization Program (NIP)…

“Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia” – Workshop

On August 01, 2022, Curatio International Foundation in the frame of the project: “Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia” held a workshop with relevant stakeholders. The purpose of the workshop was to present to the audience and…

Strengthening the Delivery of Immunisation Services Through PHC Platforms-Workshop

On July 26-27, a Linked workshop on Strengthening the Delivery of Immunisation Services Through Primary Healthcare (PHC) Platforms was successfully held by Curatio International Foundation. The collaborative learning session was held with the involvement of seven countries across the Europe-Central…

Call for internship 2022

About host organization Curatio International Foundation (CIF) is a not-for-profit, non-governmental organization with a mission to improve health through better functioning health systems. CIF’s work is underpinned by three core values: Hearing Needs, Building on Local Strength; and Delivering Innovative…

New Article published in the journal Frontiers in Public Health

In June 2022, a multidisciplinary open-access journal Frontiers in Public Health published an article: The State of Public health education and science during and after the fall of the Soviet Union: achievements, remaining challenges, and future priorities, by George Gotsadze,…

New Paper: A transdiagnostic psychosocial prevention-intervention service for young people in the Republic of Georgia

CIF researchers in collaboration with partners from GIP-Tbilisi and Cardiff University published new scientific article in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology. The article entitled “A transdiagnostic psychosocial prevention-intervention service for young people in the Republic of Georgia: early results of…

Vaccine Procurement and Supply for the Expanded Program of Immunization in Kazakhstan

In May 2022 UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN’S FUND (UNICEF) Kazakhstan published a report entitled: “Vaccine Procurement and Supply for the Expanded Program of Immunization in Kazakhstan: Gaps and Challenges for Action”, authored by Dr. George Gotsadze and Dr. David Sulaberidze, both…

Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd) – Workshop

On May 19 – 20, 2022, Curatio International Foundation held a workshop in the frame of the research project:” Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd)”. The project aims to improve the health and well-being of adolescents…

Workshop to discuss the risk assessment of future TB migrants

Curatio International Foundation held a workshop aiming to discuss: “The risk assessment of future TB migrants and offer a mechanism to reduce those risks based on advanced international experience” considering the Georgian context. Various stakeholders attended the meeting, from both…

Webinar : Matters of Scale and Integration in Digital Health Ecosystems

On February 28th, Curatio International Foundation participated in the webinar “Matters of Scale and Integration in Digital Health Ecosystems”, a part of the Digital Dialogue Series on Mixed Health Systems held by. During the webinar, the president of Curatio International…

Immunisation Action Network

Curatio International Foundation (CIF) in partnership with The Institute for Health Policy (IHP), and Results for Development (R4D) will co-lead the Linked Immunisation Action Network. CIF will serve as the focal point for six countries in the Europe and Central Asia region,…

Data Analysis and Synthesis Workshop – analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility

On January 17-21, 2022, the Curatio International Foundation held Data Analysis and Synthesis Workshop in the frame of the project: “Concentration and fragmentation: analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility (ConFrag)“. The…

External Reference Pricing Policy: A Possible Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Policy in Georgia

rmaceutical expenditure is a heavy financial burden and one of the factors of the impoverishment of the Georgian population. One of the leading factors contributing to the particularly high medicine expenditure in Georgia is a significant gap in pharmaceutical policy…

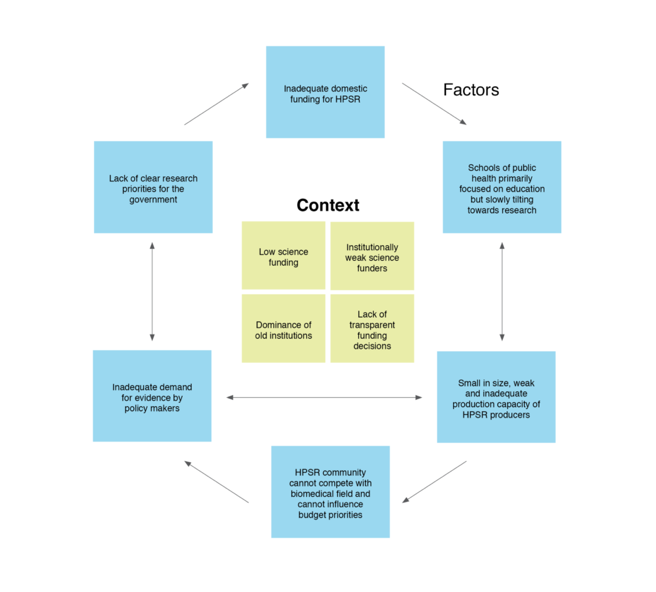

Rapid reviews of health policy and systems evidence

Rapid reviews of health policy and systems evidence provide relevant and actionable evidence at every step of the decision-making process. The Alliance established the Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Systems Decision-Making (ERA) initiative to build rapid review production directly within…

Paper: Soviet legacy is still pervasive in health policy and systems research in the post-Soviet states

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Strategic Fellowship – series of training courses for students

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Georgian NIP faces challenges in sustaining the outcomes achieved

On October 18, 2021, The Learning Network for Countries in Transition (LNCT) published new case study lessons learned: Lessons Learned from Georgia’s Experience Transitioning From GAVI support authored by: Ivdity Chikovani, Curatio International Foundation, Georgia Paata Imnadze, Deputy General Director,…

Enroll to the CIF’s Strategic Fellowship Programme

Curatio International Foundation in collaboration with the American University of Beirut, announces an educational Fellowship Program for professionals interested and active in the field of healthcare, for people who want to become advocates for change. The program is being implemented…

Article: How do participatory methods shape policy? Applying a realist approach to the formulation of a new tuberculosis policy in Georgia

The paper presents the iterative process of participatory multistakeholder engagement that informed the development of a new national tuberculosis (TB) policy in Georgia, and the lessons learned. The article was published in BMJ Journals, authored by researchers from Curatio International…

Bundled Payment Methods: An Alternative Payment Method to Contain Healthcare Costs in Georgia

Containing healthcare costs remains one of the priority topics of the Georgia health system from the perspectives of both the public and private sector. Government expenditure on health has been increasing between 2013-2019 after the introduction of the Universal Health…

DRUG CHECKING: An Essential Response to Emerging Harm Reduction Needs

Georgia has observed increasing trends of use of new psychoactive substances (NPS), as well as increased rates of non-injecting drug use in recreational settings, based on the latest available evidence. Additionally, the circulation of unknown NPS poses significant risks to…

GEORGIA COVID-19 VACCINE COMMUNICATIONS CAMPAIGN TO ADDRESS HESITANCY ISSUES

Authors: Ina Charkviani, Journalist and Communications Specialist, Curatio International Foundation and Lela Sturua, Head of Non-Communicable Disease Department, National Center for Disease Control (NCDC) of Georgia As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to shake the globe, signs of hope are beginning…

Supporting Evidence-Informed Policy making and Action in Six WHO Regions

On March 31, 2021, the Curatio International Foundation participated in HSR2020 final phase session on Innovative Models of Institutional Arrangements to Support Evidence-Informed Policy making and Action in Six WHO Regions. In this session, Curatio International Foundation as a European…

Georgian Healthcare Barometer XIV Wave The analysis of financial stability and risks in healthcare

Curatio International Foundation publishes the new 14th wave of the healthcare barometer which analyzes the financial situation and risks in Georgian healthcare sector. The new barometer has been prepared under the framework of cooperation between the Curatio International Foundation and…

Call for educational Strategic Policy Fellowship Program

Curatio International Foundation, in collaboration with the American University of Beirut, is announcing an educational Strategic Policy Fellowship Program for professionals working and active in the health field, for people who want to become advocates for change. The program is…

We are pleased to announce that The Sixth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2020) has opened

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Discussing interim results of research project: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd)

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Effects of Pay for Performance on utilization and quality of care among Primary Health Care providers in Middle and High-Income countries

Curatio International Foundation experts reviewed Pay for Performance (P4P) effectiveness on utilization and quality of primary health care in private settings in middle-income and high- income countries. About P4P Pay for Performance (P4P) is a relatively new strategy aiming at…

Does pay for performance work to improve immunization coverage?

Authors: Ivdity Chikovani Pay for Performance (P4P) is a financing mechanism that has flourished in recent years as countries look for innovative ways to improve coverage of health services. P4P can be employed as an approach to incentivize health care…

CAN SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING LEAD TO IMPROVED PERCEPTIONS ABOUT IMMUNIZATION?

Authors: Eka Paatashvili, Gayane Sahakyan (MoH, Armenia), Svetlana Grigoryan (MoH, Armenia) The recent COVID-19 crisis has shown how social media can be used successfully for community engagement and emotional support, as well as for providing the latest global evidence. Yet,…

The first phase of the joint fellowship program of the Curatio International Foundation and the Knowledge to Policy Center (K2P) at the American University of Beirut has been successfully implemented

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

LNCT WEBINAR: Incremental Costs of Routine Immunization, Campaigns, and Outreach Services During COVID-19

CLICK HERE TO REGISTER FOR THE WEBINAR Please join us on Thursday, July 16, 2020, for LNCT webinar: Incremental Costs of Routine Immunization, Campaigns, and Outreach Services During COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted immunization services critical to the prevention of vaccine preventable…

LNCT Webinar: Assessing Bottlenecks to Adequate and Predictable Vaccine Financing

Please join us on Tuesday, June 23, 2020 for LNCT webinar, Assessing Bottlenecks to Adequate and Predictable Vaccine Financing. Diagnosing the root cause of constraints affecting the adequacy and predictability of vaccine financing is an important part of the Gavi…

LNCT WEBINAR: Designing Behavioural Strategies for Immunization in a Covid-19 Context

Please join us on Thursday, May 21, 2020 for an LNCT webinar, ‘Designing Behavioral Strategies for Immunization in a Covid-19 Context.’ Hosted by Common Thread, this webinar will review the Covid-19 context that many GAVI countries now find themselves in….

Concentration and fragmentation: analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility (ConFrag)

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

LNCT Discussion Group: COVID-19 Impact on Immunization Programs

With the COVID-19 pandemic straining health systems around the world, LNCT would like to support countries to minimize potential negative effects on their immunization programs. To understand the challenges posed by COVID-19 on immunization in LNCT countries and exchange on…

#COVID19 – Evidence and Policymaking: Personal Reflections from an LMIC Setting

by George Gotsadze, President of Curatio International Foundation and Executive Director of Health Systems Global As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding…

The COVID-19 epidemic in Georgia Projections and Policy Options

Curatio International Foundation continues to support the Georgia government by providing evidence for evidence-informed decision making. Current effort – a Rapid Response document – represents an evidence synthesis about effective measures to respond to the COVID-19 epidemic. Since the epidemic…

Modeling of Four Possible Scenarios of COVID-19 epidemics in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Application for Summer Internship program is closed

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

LNCT Webinar: Key Considerations for Integrating Immunization with Other Primary Health Care Services

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Georgia Sharing knowledge to Armenia to strengthen immunization legislation

Armenia and Georgia, members of Learning Network for Countries in Transition (LNCT) participated in the twinning program on immunization legislation In February 2020. The twinning program was hosted by Curatio International Foundation. Armenian delegation represented by the Ministry of Health…

Call for Interns as researchers is now open

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Improving access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia

Curatio International Foundation conducted a policy dialogue meeting about Pharmaceutical Pricing Policies to improve the population’s access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia. The meeting was attended by various stakeholders from government agencies, non-governmental organizations, pharmaceutical companies associations. Field experts were also…

LNCT Webinar: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy Challenges

Please join us on February 6th for a webinar featuring country experiences related to vaccine hesitancy challenges. Panelists from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine will present a summary of the key issues and lessons learned during LNCT’s vaccine…

Project on “Technical Assistance Using Modern Technology for TB Prevention, Diagnosis, and Increased Quality Treatment” was closed

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Dialogue on Pharmaceutical pricing policies to improve the population’s access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

LNCT Webinar: Implementing a High Performing Immunization Program within the Context of National Health Insurance: What can we Learn from Thailand?

Please join us on Wednesday, December 11th for LNCT webinar, ‘Implementing a High Performing Immunization Program within the Context of National Health Insurance: What can we Learn from Thailand?’ Since the adoption of the National Health Security Act in 2002, all Thai citizens…

LNCT Webinar: Strengthening Public-Private Engagement for Immunization Delivery

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Implementing new research: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Georgia’s introduction of the Hexavalent vaccine: Lessons on successful procurement and advocacy

Authors: Eka Paatashvili and Vladimer Getia As countries transition from Gavi support, sustaining access to affordable and high-quality vaccines is one of many challenges they face. Fully self-financing countries need to maintain their immunization programs while also committing increased funds…

Georgia Primary Health Care Profile: 6 Year after UHC program introduction

Curatio International Foundation publishes Georgia Primary Health Care (PHC) profile. Georgia PHC profile was prepared based on Primary Health Care Vital Signs framework developed by the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI). PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transform the…

National consultations to propose a new model of TB funding

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

HSR2020: RE-IMAGINING HEALTH SYSTEMS FOR BETTER HEALTH AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

We are pleased to announce the theme and sub-themes for the Sixth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Dubai in November 2020: “Re-imagining health systems for better health and social justice” Ten years on from the First Global Symposium on Health Systems…

CALL FOR MENTEES: PUBLICATION MENTORSHIP FOR FIRST-TIME WOMEN AUTHORS IN THE FIELD OF HPSR

Health Systems Global (HSG) and The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (AHPSR) are committed to supporting individual capacity for the conduct and uptake of health policy and systems research (HPSR). Peer reviewed publications are important for communicating scientific…

A pilot of a new intervention launched to Improve adherence to TB treatment and its outcomes in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Training for epidemiologists and health workers on TB contact tracing new guideline

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Workshop on using modern technology for TB prevention, diagnosis and increased quality treatment

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

K2P Mentorship Program on Building Institutional Capacity on Evidence Informed Policy Making

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Training on using Research Evidence for Policy Making

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Doing embedded development and research – reflections on the start of the Results4TB programme

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Healthcare Advocacy Coalition (HAC) for Human Oriented Healthcare

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Introductory Meeting on the project ‘Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Policy-Making’

On November 5, the Committee on Health and Social Affairs of the Parliament of Georgia will host an introductory meeting on the project Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Policy-Making. The project is jointly implemented by the “Curatio International Foundation” and…

Taavy Miller from University of North Carolina shares her internship experience

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Building Institutional Capacity for HPSR and Delivery Science- CIF is Europe region HUB

General Overview The evidence-informed decision making in health still remains a major challenge. To strengthen institutional capacity in different countries around the globe the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (AHPSR) launched the new program to strengthen the capacity…

Inter-regional workshop in preparation for transitioning towards domestic financing in TB, HIV and Malaria programmes

During October 17-19 the WHO Regional Office for Europe in collaboration with WHO headquarters, GFATM and USAID organised a workshop in Tbilisi to provide countries a platform for dialogue on sustainability and transition issues, and to further define regional and…

Memorandum of Cooperation between the Health and Social Issues Committee of the Parliament of Georgia and Curatio International Foundation

Chairman of the Health Care and Social Issues Committee of the Parliament of Georgia Akaki Zoidze and Curatio International Foundation President George Gotsadze signed a memorandum of cooperation. The collaboration aims to support evidence usage by the parliament when dealing with the…

Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Systems Decision-Making (ERA)

General Overview As a result of the constitutional amendments passed at the end of 2017, Georgia became a parliamentary republic. It increased the role of the legislature in policy development and supervision. As a result of these amendments, the Committee…

Curatio International Foundation at the Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

During October 8-12, 2018 Liverpool hosted the Fifth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research. Curatio International Foundation, as a secretariat of Health Systems Global, organzied the event for the second time in close collaboration with HSG’s partners. Over 2300 participants from…

The civil society gathered for the fourth time to discuss healthcare system challenges in Georgia

On September 27-29, the fourth work meeting of a civil society was held in Kachreti. Representatives of a civil society, media, and academia convene under the framework of the joint project of Curatio International Foundation and Open Society Foundation. The…

Project: HIV risk behavior among Men who have Sex with Men – Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey and Population Size Estimation

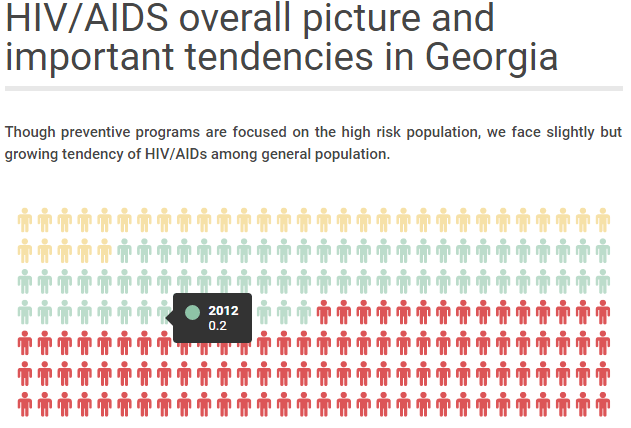

Introduction and Overview Georgia is among the countries with low HIV/AIDS prevalence but with a high potential for the development of a widespread epidemic. From the early years of the epidemic injecting drug use was the major route for HIV transmission,…

Curatio International Foundation at AIDS2018

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Big Pharma Greed and Artificial Prices – Knocking on Door to Limit Access to HIV Medicines in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Civil society is gathering for the third time to hold a discussion about the healthcare

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Webinar: Mapping and consensus of global competencies set for the field of HPSR: A progress update and HSG round table discussion

This webinar took place on July 11th, 2018. If you missed it or would like to listen to it again, you can watch the recording. Are you involved with designing HPSR training programs? Do you create course content for HPSR training?…

Webinar: Vaccine Forecasting and Budgeting Tools and Best Practices

This webinar took place on July 2, 2018. However, if you missed the webinar or would like to listen to it again, you can watch the recording and download the slides. Participants will learn about existing vaccine forecasting and budgeting tools and best…

Technical Assistance for evaluation of transition readiness and preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for Global Fund-supported programs in Tajikistan

Introduction and Overview In June 2018 CIF initiated a new project with the financial support of The Global Fund. The overall goal of the CIF assignment is to support the Country Coordination Mechanism of Tajikistan (CCM) in assessing country preparedness…

Technical Assistance for the preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for HIV program in Philippines

Introduction and Overview Since May 2018 Curatio International Foundation implements a technical assistance for the Philippines to prepare Transition and Sustainability Plan for HIV program. The overall goal of the given assignment is to support the Department of Health and…

Discussing the accessibility of medicines in Georgia

Curatio International Foundation, within the framework of the ongoing project: “Engaging civil society in decision-making and monitoring in Georgian healthcare sector” supports strengthening and consolidating civil society representatives interested in health care for advocacy on health issues. To this end,…

Webinar: Integrating gender into health system strengthening in conflict and crisis-affected settings; what’s in our toolkit?

This webinar took place on June 22, 2018. However, if you missed the webinar or would like to listen to it again, you can watch the recording and download the slides. In 2016, HSG held the first webinar on gender, asking the question, “What…

Article: Barriers to mental health care utilization among internally displaced persons in the republic of Georgia: a rapid appraisal study

The new paper identifies the health system barriers leading to low rates of utilization of mental health services among internally displaced people (IDP) with mental disorders. The paper was published in BMC Health Services Research authored by Adrianna Murphy, Ivdity…

Why Georgians second-guess their doctors – Deregulation has left Georgian medical care something many Georgians would rather avoid

Full Article is available on Eurasianet ” […] Last year, Giorgi Tsiklauri, 24, was diagnosed with leukemia at a hospital in Tbilisi and was about to undergo chemotherapy, but he decided to seek a second opinion in Turkey. As it…

Ara Srinagesh from New York University Shares her Internship Experience

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Webinar on The peer review process – what happens when you send your manuscript to a journal

This webinar took place on April 23, 2018. However, if you missed the session or want to listen to it again, you can watch the recording. Have you ever wondered what the journal editor’s viewpoint is on your article, or what…

Webinar on Improving Quality of Care during Childbirth: Learnings and Next Steps from the BetterBirth Trial

This webinar took place on April 24, 2018. However, if you missed the session or want to listen to it again, you can watch the recording. Join the webinar organized by HSG Thematic Working Group Quality in Universal Health and Healthcare. During…

Civil Society is Being United to Discuss Healthcare System Issues

Curatio International Foundation, within the framework of the ongoing project: “Engaging civil society in decision-making and monitoring in Georgian healthcare sector” along with the Open Society Network supports strengthening and consolidating civil society representatives interested in health care for advocacy…

Curatio International Foundation for a TB-Free World

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Summer Internship Program is now open

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Closing Project: Tuberculosis Community Systems Strengthening in Georgia

The Curatio International Foundation has fulfilled a Tuberculosis Community Systems Strengthening (TBCSS) Project in Georgia, funded by the Stop TB partnership in the frame of Challenge Facility for Civil Society (CFCS) round 7 program. The goal for the project was…

Primary Health Care Systems: Georgia case study

Curatio International Foundation publishes Georgia case study of primary health care system (PRIMASYS). The PRIMASYS case study covers key aspects of primary health care system, including policy development and implementation, financing, integration of primary health care into comprehensive health systems,…

Integrated Bio-behavioral surveillance and population size estimation survey among Female Sex Workers in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia

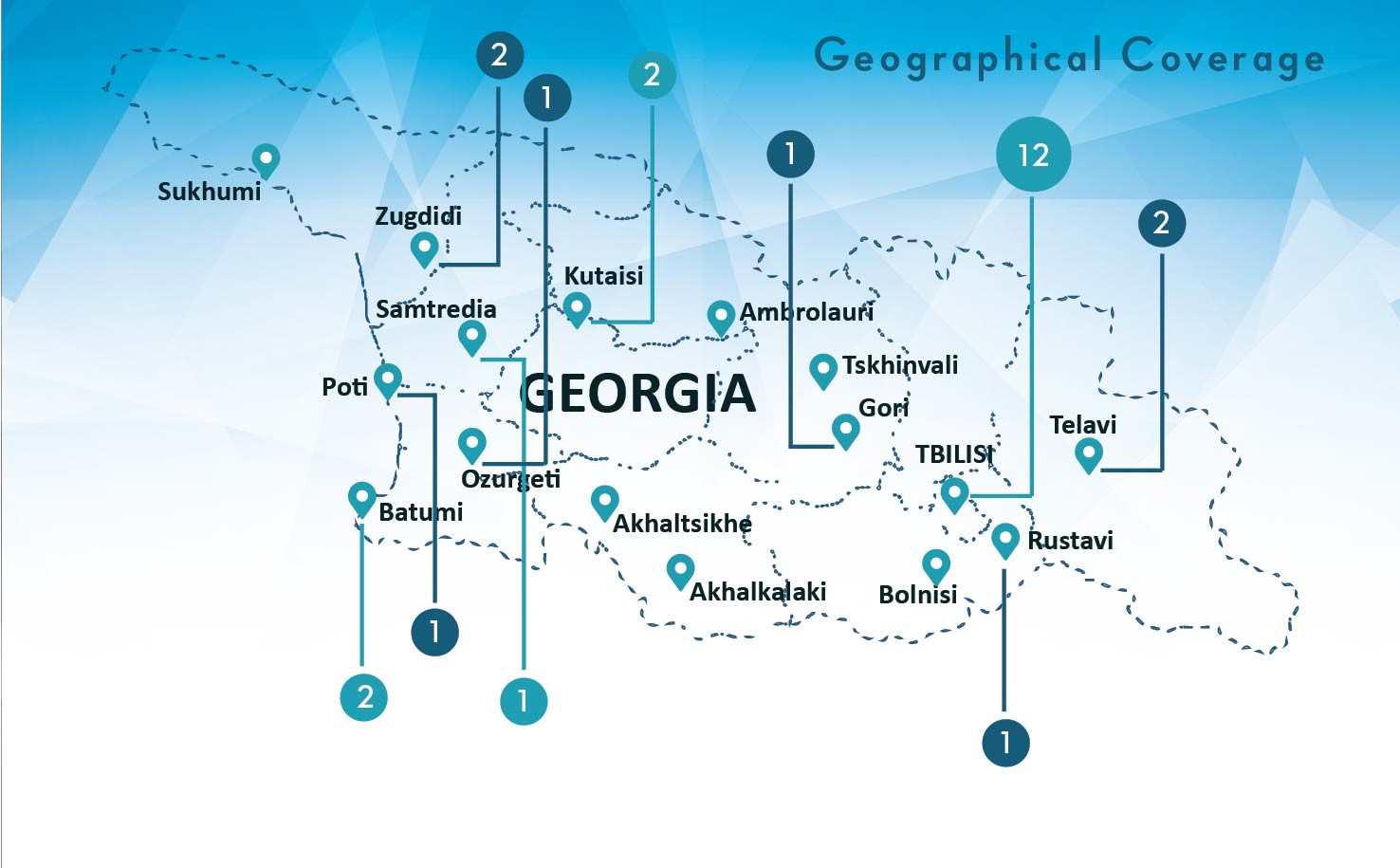

This study represents the subsequent wave of Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (BBS) surveys undertaken among Female Sex Workers (FSW) since 2002. The current study was conducted in 2017 using the Time-Location Sampling technique and 350 FSWs was recruited in total in…

Applying a Health Policy and Systems Research lens to Human Resources for Health: Capacity building, leadership and politics

This webinar took place on March 14, 2018. However, if you missed the webinar or want to listen to it again, you can watch the recording and download the slides. How do we study ‘invisible’ concepts such as politics and power as they…

CIF hosts Aradhana Srinagesh throughout the winter internship program

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Empowering civil society for engagement in and monitoring the decision making in health sector in Georgia

Introduction and Overview The project aims to strengthen CSOs working on Health Systems to participate in the decision-making process, to assume watchdog functions, monitor enforcement of policies and advocate for better health for all. The project is funded by Open Society…

Curatio International Foundation presented BBS and PSE study findings at the Civil Society Forum

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

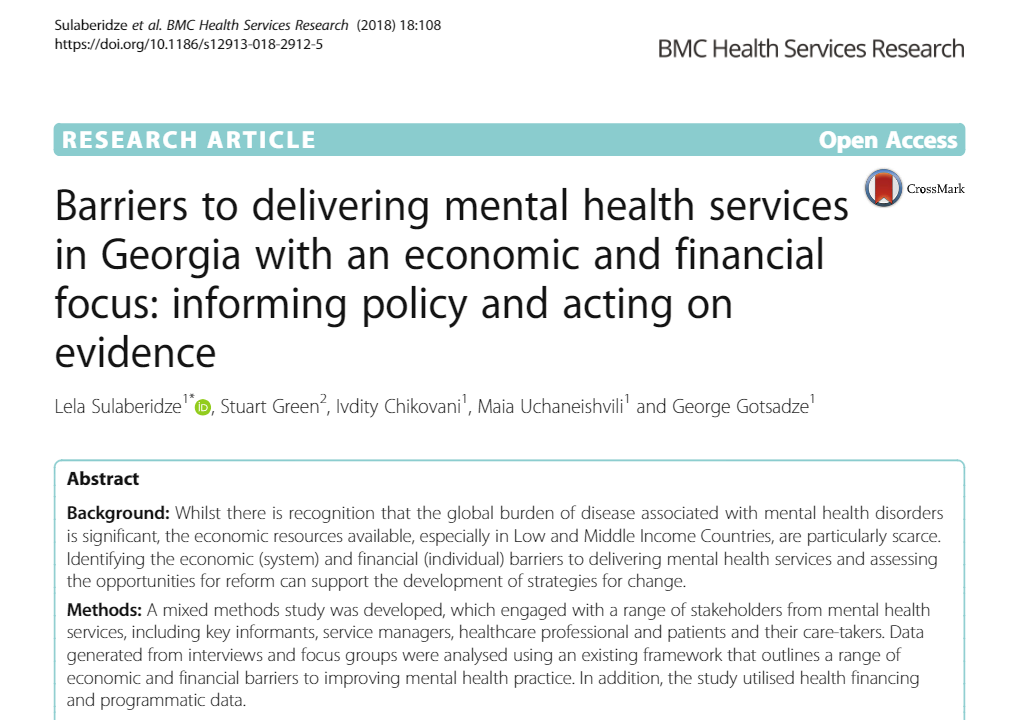

Article: Barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia with an economic and financial focus: informing policy and acting on evidence

A new paper discusses the economic and financial barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia and assessing the opportunities for reform that can support the development of strategies for change. The article was published in BMC Health Services Research,…

The Interview on population size and Human Immunodeficiency Virus risk behaviors of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia

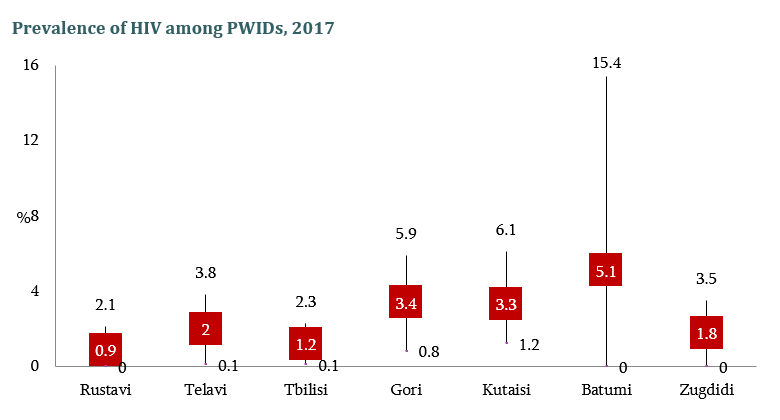

The interview is based on the latest wave of the integrated Bio- behavioral surveillance survey conducted People Who Inject drugs (PWID) in 7 cities of Georgia. The research aims to measure the prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis…

Population Size Estimation of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia 2016-2017

Bemoni Public Union together with Curatio International Foundation conducted a population size estimation study among injecting drug users in Georgia during 2016-2017. Also available: HIV risk and prevention behaviors among People Who Inject Drugs in six cities, Georgia, 2017 This…

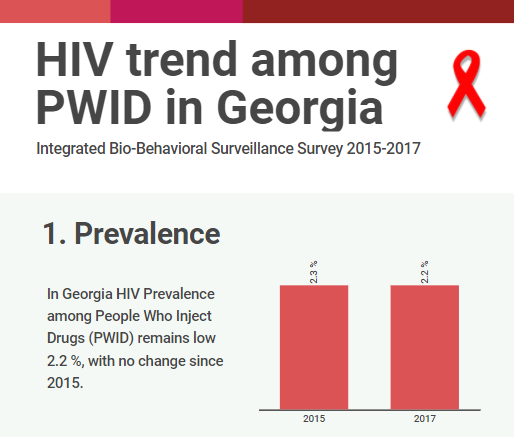

HIV risk and prevention behaviors among People Who Inject Drugs in seven cities of Georgia, 2017

Curatio International Foundation together with Bemoni Public Union has conducted HIV prevalence and risk behaviors survey among People Who Inject Drugs in Georgia. Also available: Population Size Estimation of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia 2016-2017 Current study represents the…

Conference paper: The Study of Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment among Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients in Georgia to Inform Policy Decision

The abstract has been submitted and accept for oral presentation at The Union 2017 – 48th Union World Conference on Lung Health, 11 – 14 October, 2017 Guadalajara, Mexico The study outlines different health system factors as long as some…

Article: Human immunodeficiency virus prevalence and risk determinants among people who inject drugs in the Republic of Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Conference paper about realist evaluation: Informing policy, assessing its effects and understanding how it works for improved Tuberculosis management in Georgia

In the last week of October, 2017 Brisbane, Australia hosted International Conference for Realist Research Evaluation and Synthesis – Realist2017. Realist evaluation is complex sensitive approach and is useful for decision makers because rather responding the question “does the intervention…

Georgian Healthcare and its Challenges: Healthcare Expert George Gotsadze will host the lecture

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

17 years in Curatio International Foundation: President Ketevan Chkhatarashvili to Leave Organization

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Be ready for the Best Internship Experience

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Apply for Our Winter Internship Program

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Georgian Solution for a Post-Soviet TB Program: Can Integration into Primary Health Care Improve TB Care?

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Moving Forward: Second PT workshop with TB stakeholders in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Article: Determinants analysis of outpatient service utilization in Georgia: can the approach help inform benefit package design?

Curatio International Foundation conducted secondary data analyses of Health Service Utilization and Expenditure survey (2 waves), conducted by Ministry of Labor Health and Social Affairs of Georgia, supported by WHO and The World Bank. We studied factors that impact utilization…

Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in Georgia (RBF4TB)

Introduction and Overview CIF in partnership with Queen Margaret University (UK), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK) and Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine (Belgium) is implementing a study “Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in…

Forbes Georgia: The Importance of Evidence in Decision Making

In February 2017, CIF director George Gotsadze talked with Forbes Georgia. The interview discusses the role of effective management in health systems and impact of innovations in the field. In the article George speaks about CIF experience serving as HSG Secretariat. Read more…

Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment Among Drug Resistant TB Patients in Georgia

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Transition Preparedness Assessment

Sustainability of national HIV and TB programs gains importance in light of recent changes in the global health landscape when external funders are redirecting resources to poorer states while phasing out from middle-income countries. Objectively evaluation of the country transition…

New Study Findings About Tuberculosis

Curatio International Foundation together with the Partnership for Research and Action for Health organized a meeting at the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health on 26th of December, where two different study findings were represented. Studies aimed to…

Meet CIF in Vancouver at HSR2016

Curatio International Foundation will be featured at Health Systems Research 4th Symposium to be held in Vancouver, Canada November 14 -18, 2016. CIF experts will discuss several important health system-related issues and share particular knowledge with a global audience. We…

Curatio International Foundation: Transition and Sustainability Portfolio

As middle-income countries experience economic growth and increased government spending potential on healthcare, donors have begun decreasing their support under the assumption those countries have sufficient physical space to support and sustain their health programs. Countries in Eastern Europe and…

Article: Privilege and inclusivity in shaping Global Health agendas

Health Policy and Planning published an article Privilege and inclusivity in shaping Global Health agendas. CIF director George Gotsadze co-authors the paper together with Kabir Sheikh, Sara Bennett and Fadi el Jardali. The article discusses lack of inclusivity in Global Health…

Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regional Sustainability and Transition Coordination Summit 20-21 October, 2016 Vilnius, Lithuania

In recent years there has been a significant decrease in funding from international and bilateral donors, including The Global Fund (TGF) to support HIV and TB response in middle income countries across Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA). This raises…

Internship Announcement, Winter 2016-17

Author: Eka Paatashvili Over this last year, countries around the world have been forced to focus most of their efforts on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially leaving other health priorities, including routine immunization, to fall by the wayside. To understand...

Evaluation of UNICEF’s Contribution in Central and Eastern European Five Countries

Curatio International Foundation conducted an evaluation of UNICEF’s contribution to the reduction of under 5 mortality in five countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Serbia, and Uzbekistan. The evaluation covered 12 years from 2000 – 2012 and was performed in 2014-2015. UNICEF’s…

CIF researchers represented on Global Conference AIDS2016

CIF researchers Ivdity Chikovani and Lela Sulaberidze participated in AIDS 2016 conference that was held in Durban, South Africa in July 2016. The conference assembled over 18,000 delegates from around the world. Scientists, policymakers, world leaders, and people living with…

CIF Pharmaceutical Price and Availability Study (Fifth Wave Results)

The Curatio International Foundation has released the results of the fifth wave of the Pharmaceutical Price and Availability (PPA) study in Georgia. The study set out to generate further evidence regarding pharmaceutical prices and availability in the country through the…

Assessment of GAVI Alliance HSS support to Tajikistan

In August 2014, Curatio International Foundation conducted an assessment of GAVI Alliance HSS support to Tajikstan to provide solid evidence of to what extent the support achieved its objectives and contributed to strengthen the health system of the country. The assessment…

Final Evaluation of Gavi’s Support to Albania

After the conclusion of Gavi’s support period (2014) to the Albania, Curatio International Foundation conducted the evaluation study and assessed financial and programmatic sustainability through an in-depth analysis of Albania’s experiences and immunization programme performance before, during and after the…

HIV risk and prevention behaviours among Prison Inmates in Georgia, 2015

Curatio International Foundation continues implementation of Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (BBS) among Key Affected Populations (KAP’s) with the aim to measure HIV prevalence among KAP’s, monitor risk behaviors among these groups and generate evidence for advocacy and policy-making. The current study…

Washington DC hosts workshop Immunization Costing: what have we learned, can we do better?

On May 17-18 EPIC Immunization Costing hosts workshop Immunization Costing: what have we learned, can we do better? in Washington DC. CIF executive director George Gotsadze and Business Develop ment unit director Ketevan Goguadze are invited to attend the event. George Gotsadze…

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among Men who have Sex with Men in two major cities of Georgia, 2015

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among Men who have Sex with Men in two major cities of Georgia, 2015 Curatio International Foundation continues implementation of Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (BBS) among Key Affected Populations (KAP’s) with the aim to measure HIV prevalence among…

EPIC Studies – Governments Finance, On Average, More Than 50 Percent Of Immunization Expenses, 2010–11

Journal Health Affairs publishes a new Article EPIC Studies: Governments Finance, On Average, More Than 50 Percent Of Immunization Expenses, 2010–11 coauthored by CIF team member Keti Goguadze. Abstract: Governments in resource-poor settings have traditionally relied on external donor support…

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among People Who Inject Drugs in 7 cities of Georgia, 2015

Curatio International Foundation continues implementation of Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (BBS) among Key Affected Populations (KAP’s) with the aim to measure HIV prevalence among KAP’s, monitor risk behaviors among these groups and generate evidence for advocacy and policy-making. The current study…

TB Community Systems Strengthening in Georgia

We are glad to announce that Curatio International Foundation has been selected to be Round 7 Challenge Facility for Civil Society (CFCS) grantee under the Stop TB partnership financial support. TB Community Systems Strengthening (TBCSS) project in Georgia aims –…

What can be done to improve treatment adherence among tuberculosis patients in Georgia: Looking through health systems lens

Curatio International Foundation has started implementation of new research project with the aim to provide a more in-depth understanding of the factors associated with loss to follow-up among TB patients. The project is funded under the Joint TDR/EURO Small Grants…

BioBehavior Surveillance Survey results were represented to the members of Parliament of Georgia

Curatio International Foundation together with BEMONI PUBLIC UNION (BPU) represented BioBehavior Surveillance Survey results to the Members of Parliament of Georgia. The study was conducted in seven major cities of Georgia (Tbilisi, Gori, Telavi, Zugdidi, Batumi, Kutaisi and Rustavi) with…

Announcing Winter Internship Program 2016

Curatio International Foundation invites Master and PhD international students to apply on Winter Internship Program. Through the program, students have the possibility to develop advanced research skills, meet leading experts in the field and become a coauthor of a scientific…

Regional High Level Dialogue ‘Road to Success’, Tbilisi, Georgia

On September 28-30, 2015 Regional High Level Dialogue took place in Tbilisi, Georgia on Successful Transition to Domestic Funding of HIV and TB Response in EECA. The 320 delegates from 31 countries have agreed to work together in creating and…

CIF study results on 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention

Findings of population size estimation study among Man who have Sex with Men (MSM) was presented to the 8th International Aids Association conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention in Vancouver, Canada in July, 2015. The study was conducted by…

Response to the “Final evaluation of GAVI support to Bosnia and Herzegovina”

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance published response to the “Final evaluation of Gavi support to Bosnia and Herzegovina” conducted by Curatio International Foundation. Gavi assess the final evaluation and the given recommendations as an important document for the transition country program…

The drivers of facility-based immunization performance and costs. An application to Moldova

The drivers of facility-based immunization performance and costs. An application to Moldova. This is the article an International peer reviewed Journal Vaccine published, Co-authored by experts from the Curatio International Foundation. The study was a part of a multi-country coting and…

Awaiting the results of Prisoners’ Behavior Surveillance Survey (BSS)

Curatio International Foundation together with Infectious Diseases, AIDS and Clinical Immunology Research Center and Association Tanadgoma has conducted the Behavior Surveillance Survey with biomarker component. The study report of Behavior Surveillance Survey with biomarker component among 210 prisoners will be…

Costs of routine immunization services in Moldova: Findings of a facility-based costing study

An International peer reviewed Journal Vaccine, published an article Costs of routine immunization services in Moldova: Findings of a facility-based costing study. Authored by experts from the Curatio International Foundation. The study evaluates the total economic and unit costs of…

Analyses of Costs and Financing of the Routine Immunization Program and New Vaccine Introduction in the Republic of Moldova

In 2012-2014 Curatio International Foundation implemented the costing study that aimed to evaluate routine immunization program costs and financing as well as incremental costs and financing of a new vaccine introduction in the Republic of Moldova. The study was a…

Health Service Utilization for Mental, Behavioural and Emotional Problems among Conflict-Affected Population in Georgia

An International peer reviewed Journal PLOS One has published an article Health Service Utilization for Mental, Behavioral and Emotional Problems among Conflict-Affected Population in Georgia: A Cross-Sectional Study, authored by experts from the Curatio International Foundation, and the London School of…

Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures for Chronic and Acute Conditions in Georgia: Does benefit package design matter?

An International peer reviewed journal BMC Health Services Research publishes an article Healthcare utilization and expenditures for chronic and acute conditions in Georgia: Does benefit package design matter?, authored by experts from the Curatio International Foundation and London School of…

Curatio International Foundation Hosts Health Systems Global Secretariat in Tbilisi, Georgia

Curatio International Foundation Hosts Health Systems Global Secretariat in Tbilisi, Georgia. Health Systems Global (HSG) is the first international membership organization fully dedicated to promoting health systems research and related knowledge translation. HSG brings together researchers, policy-makers, funders, implementers, civil…

An Impact Evaluation of Medical Insurance for Poor in Georgia: Preliminary Results and Policy Implications

An International peer reviewed journal Health Policy and Planning has published an article An impact evaluation of medical insurance for poor in Georgia: preliminary results and policy implications, authored by Curatio International Foundation experts. The authors evaluated the impact of…

Policy Information Platform (PIP) Expert Consultation Meeting

Policy Information Platform (PIP) expert consultation was held in Istanbul on 29-30 January, 2015. At the meeting methodological issues, roadmap for the PIP implementation and evaluation approaches were discussed. CIF director George Gotsadze and Research Unit director Ivdity Chikovani participated…

Civil Society Forum organized by Country Coordination Mechanism

On January 29, at Courtyard Marriott Hotel was held a Civil Society Forum organized by Country Coordination Mechanism. The forum was part of country dialogue process regarding HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis issues. During the meeting, civil society representatives shared results of…

CIF Publishes the Short Movie on 20 Years of Healthcare, 2014

Curatio International Foundation celebrates its 20 years anniversary and prepares short movie describing the history of health care reforms in Georgia after collapse of Soviet Union. The story is retailed directly by the people involved in the process and organizations…

CIF Publishes Anniversary Publication ’20 Years of Health Care, 2014

20 Years Anniversary brochure describes reforms that have significantly altered the landscape of health care in Georgia after collapse of the Soviet Union. The contents draw on important publications and oral narratives by those who have been initiators, implementers and witnesses to…

CIF Celebrated the 20th Anniversary

On September 19, Curatio International Foundation celebrated the 20th anniversary. Alongside with our work it turned 20 years from Georgian healthcare system reforming start up, after collapse of Soviet Union. CIF celebrated the anniversary together with the people who were…

Georgian Healthcare System Barometer: Experts’ Evaluations of Changes Taking Place in the Healthcare

Curatio International Foundation published results of the survey, representing expert evaluations of processes and changes taking place in the Georgian healthcare field. “Georgian Healthcare System Barometer” is based on evaluations of 98 experts and covers 6-month period – May-October, 2013….

BlogTalkRadio to Host CIF President

In October 2013, the BlogTalkRadio program focusing on health hosted Katevan Chkhatarashvili, the President of Curatio International Foundation. Ketevan talks about her public health experience and CIF’s role in transition of Georgia’s health sector. New Health Internet Radio with Global…

Winner of CIF Students Fellowship Program for 2013-2014

Ana Petriashvili became the winner of Curatio International Foundation Fellowship program for 2013- 2014. As the winner of the previous year, she too is the Master program student of International Public Health Department of Tbilisi State Medical University. Ana is…

The Forbes and Skoll World Forum to discuss HIV/AIDS Epidemic with Director of CIF

Which Region Has The Fastest-Growing HIV/AIDS Epidemic In The World?- Giorgi Gotsadze, Director of Curatio International Foundation was asked to discuss this issue with Forbes. The discussion precedes many health-related discussions to take place in September at the Clinton Global…