Why Georgians second-guess their doctors – Deregulation has left Georgian medical care something many Georgians would rather avoid

Full Article is available on Eurasianet

” […] Last year, Giorgi Tsiklauri, 24, was diagnosed with leukemia at a hospital in Tbilisi and was about to undergo chemotherapy, but he decided to seek a second opinion in Turkey. As it turned out, he had an infection on the inner surface of his heart, Tsiklauri told local media, publicly accusing his Georgian doctor of incompetence.

Of course, doctors can make mistakes in even the most-developed countries. A 2017 study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine found that medical error ranks as the third-leading cause of death in the United States.

But the statistics suggest Georgia has a large number of poorly regulated doctors.

Last year, the Georgian government suspended 93 doctors’ licenses, mostly for malpractice, according to Nino Khutsishvili of the State Agency for Regulating Medical Activity. By comparison, the state of California, which has 10 times the population and five times the doctors, revoked 44 medical licenses on similar grounds.

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

“Medicine is a constantly evolving field and lifelong learning is needed to stay abreast of [changes]. In Georgia, physicians are not required by the state to keep upgrading their professional skills,” Gotsadze explained.

In a 2017 report for the World Health Organization, Curatio emphasized the risks of deregulation and the privatization of state medical facilities.

“In 2006, the government of Georgia introduced an aggressive privatization policy and applied market-regulated principles to the health sector, characterized by liberal regulations and minimum supervision. In the framework of this policy, many regulations were abolished, and medical facilities and quality of services were no longer controlled by the state,” the report said. Today, “there are no regulations to appraise service providers’ clinical practice.”

Compensation

Even if patients ultimately escape a poorly trained doctor unharmed, many are averse to go through with the drudgery of pressing administrative and legal charges. Dentist Nino Kopadze was content to simply tell off the doctor who mistakenly diagnosed her with stomach cancer. “I did not have the stamina to follow through with filing a complaint and all that, though I should have,” she told Eurasianet.

The man who did the original ultrasound test on Kira publicly admitted his mistake. “I am of course now convinced that I made a mistake and that there was nothing there. And I have no problem apologizing for it,” the diagnostic sonographer at Interclinic said on television. (Interclinic declined to be interviewed in a reasonable timeframe for this story.) Kira’s parents are now deciding whether to accept the apology or to press for compensation for the costs and stress they suffered.”

Eurasianet is an independent news organization that covers news from and about the South Caucasus and Central Asia, providing on-the-ground reporting and critical perspectives on the most important developments in the region.

Latest News

Janina Stauke from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine shares her internship experience

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Jolly Mae Catalan fromUniversité Libre de Bruxelles shares her internship experience

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgia’s Journey to Integrating Rehabilitation Services into the Health System: Insights and Lessons

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgia: a primary health care case study in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Linked’s workshop on HPV vaccine introduction and scale up, held on July 11-12th, 2023

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Training program focusing on interdisciplinary evaluation of rehabilitation interventions and patient outcomes

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Unlocking Success Through Learning: Workshop on Strengthening HR Capacity and Performance Management in Immunization

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence and fostering civic engagement

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF and the Results for Development / Accelerator combined their expertise to co-author an insightful blog, shedding light on Georgia’s commendable efforts to overcome limited data challenges and develop evidence-based policies for financing rehabilitation services

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Culminating event – Building Institutional Capacity for Health Policy and Systems Research and Delivery science (BIRD) in six WHO Regions

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Report on Phased (Stepwise) Plan for the Capability Development of the Priority Rehabilitation Services

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Sustaining Public Health Gains after Donor Transition: What can we learn about Georgia?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation at Seventh Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2022)

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation at Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Study report: Adaptations made in TB response during Covid-19 pandemic in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

New case study: Sustaining effective coverage with Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) in Georgia in the context of transition from external assistance

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

New case study: National Immunisation Program Transition from external assistance

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

“Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia” – Workshop

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Strengthening the Delivery of Immunisation Services Through PHC Platforms-Workshop

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

New Paper: A transdiagnostic psychosocial prevention-intervention service for young people in the Republic of Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Vaccine Procurement and Supply for the Expanded Program of Immunization in Kazakhstan

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd) – Workshop

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Data Analysis and Synthesis Workshop – analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

External Reference Pricing Policy: A Possible Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Policy in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

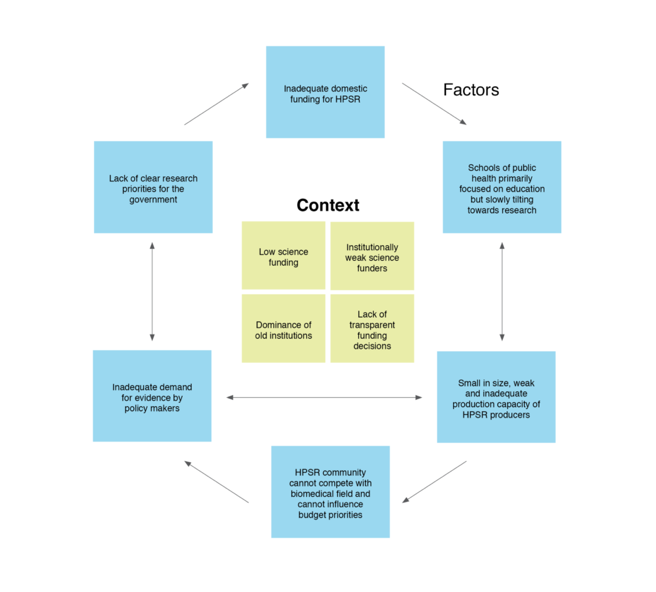

Paper: Soviet legacy is still pervasive in health policy and systems research in the post-Soviet states

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Article: How do participatory methods shape policy? Applying a realist approach to the formulation of a new tuberculosis policy in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Bundled Payment Methods: An Alternative Payment Method to Contain Healthcare Costs in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

HOW TO MAINTAIN ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION DURING COVID-19? EXPERIENCES FROM ARMENIA, GEORGIA, AND UZBEKISTAN

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgian Healthcare Barometer XIV Wave The analysis of financial stability and risks in healthcare

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

We are pleased to announce that The Sixth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2020) has opened

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Discussing interim results of research project: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd)

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Effects of Pay for Performance on utilization and quality of care among Primary Health Care providers in Middle and High-Income countries

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The first phase of the joint fellowship program of the Curatio International Foundation and the Knowledge to Policy Center (K2P) at the American University of Beirut has been successfully implemented

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT WEBINAR: Incremental Costs of Routine Immunization, Campaigns, and Outreach Services During COVID-19

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT Webinar: Assessing Bottlenecks to Adequate and Predictable Vaccine Financing

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT WEBINAR: Designing Behavioural Strategies for Immunization in a Covid-19 Context

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Concentration and fragmentation: analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility (ConFrag)

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

#COVID19 – Evidence and Policymaking: Personal Reflections from an LMIC Setting

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT Webinar: Key Considerations for Integrating Immunization with Other Primary Health Care Services

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Project on “Technical Assistance Using Modern Technology for TB Prevention, Diagnosis, and Increased Quality Treatment” was closed

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Dialogue on Pharmaceutical pricing policies to improve the population’s access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT Webinar: Implementing a High Performing Immunization Program within the Context of National Health Insurance: What can we Learn from Thailand?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

LNCT Webinar: Strengthening Public-Private Engagement for Immunization Delivery

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Implementing new research: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgia’s introduction of the Hexavalent vaccine: Lessons on successful procurement and advocacy

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CALL FOR MENTEES: PUBLICATION MENTORSHIP FOR FIRST-TIME WOMEN AUTHORS IN THE FIELD OF HPSR

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

A pilot of a new intervention launched to Improve adherence to TB treatment and its outcomes in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Training for epidemiologists and health workers on TB contact tracing new guideline

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Workshop on using modern technology for TB prevention, diagnosis and increased quality treatment

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

K2P Mentorship Program on Building Institutional Capacity on Evidence Informed Policy Making

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Doing embedded development and research – reflections on the start of the Results4TB programme

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Introductory Meeting on the project ‘Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Policy-Making’

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Taavy Miller from University of North Carolina shares her internship experience

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Building Institutional Capacity for HPSR and Delivery Science- CIF is Europe region HUB

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Inter-regional workshop in preparation for transitioning towards domestic financing in TB, HIV and Malaria programmes

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Memorandum of Cooperation between the Health and Social Issues Committee of the Parliament of Georgia and Curatio International Foundation

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation at the Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The civil society gathered for the fourth time to discuss healthcare system challenges in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Project: HIV risk behavior among Men who have Sex with Men – Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey and Population Size Estimation

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Big Pharma Greed and Artificial Prices – Knocking on Door to Limit Access to HIV Medicines in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Civil society is gathering for the third time to hold a discussion about the healthcare

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Webinar: Mapping and consensus of global competencies set for the field of HPSR: A progress update and HSG round table discussion

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Technical Assistance for evaluation of transition readiness and preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for Global Fund-supported programs in Tajikistan

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Technical Assistance for the preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for HIV program in Philippines

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Webinar: Integrating gender into health system strengthening in conflict and crisis-affected settings; what’s in our toolkit?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Article: Barriers to mental health care utilization among internally displaced persons in the republic of Georgia: a rapid appraisal study

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Webinar on The peer review process – what happens when you send your manuscript to a journal

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Webinar on Improving Quality of Care during Childbirth: Learnings and Next Steps from the BetterBirth Trial

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

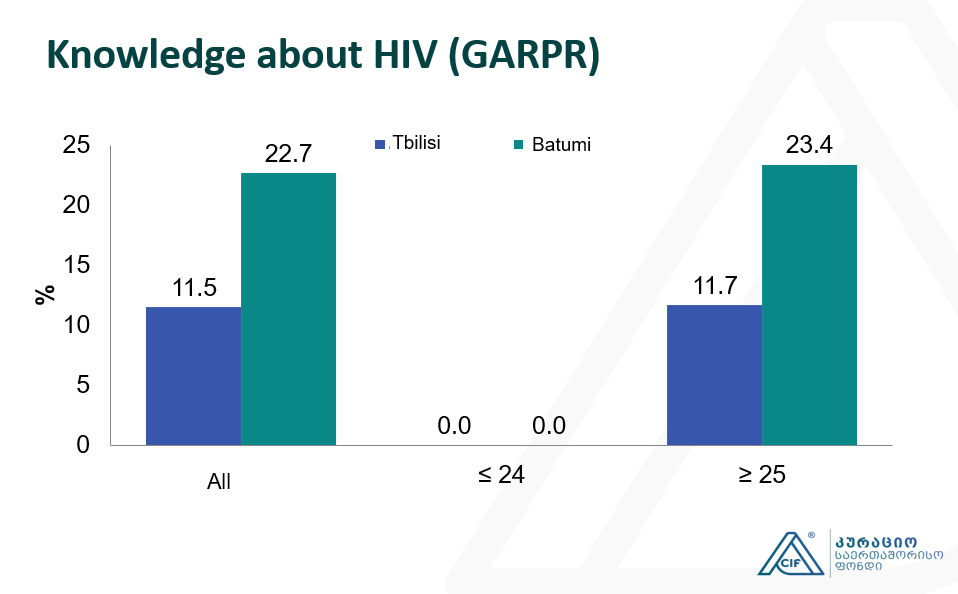

Integrated Bio-behavioral surveillance and population size estimation survey among Female Sex Workers in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Applying a Health Policy and Systems Research lens to Human Resources for Health: Capacity building, leadership and politics

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

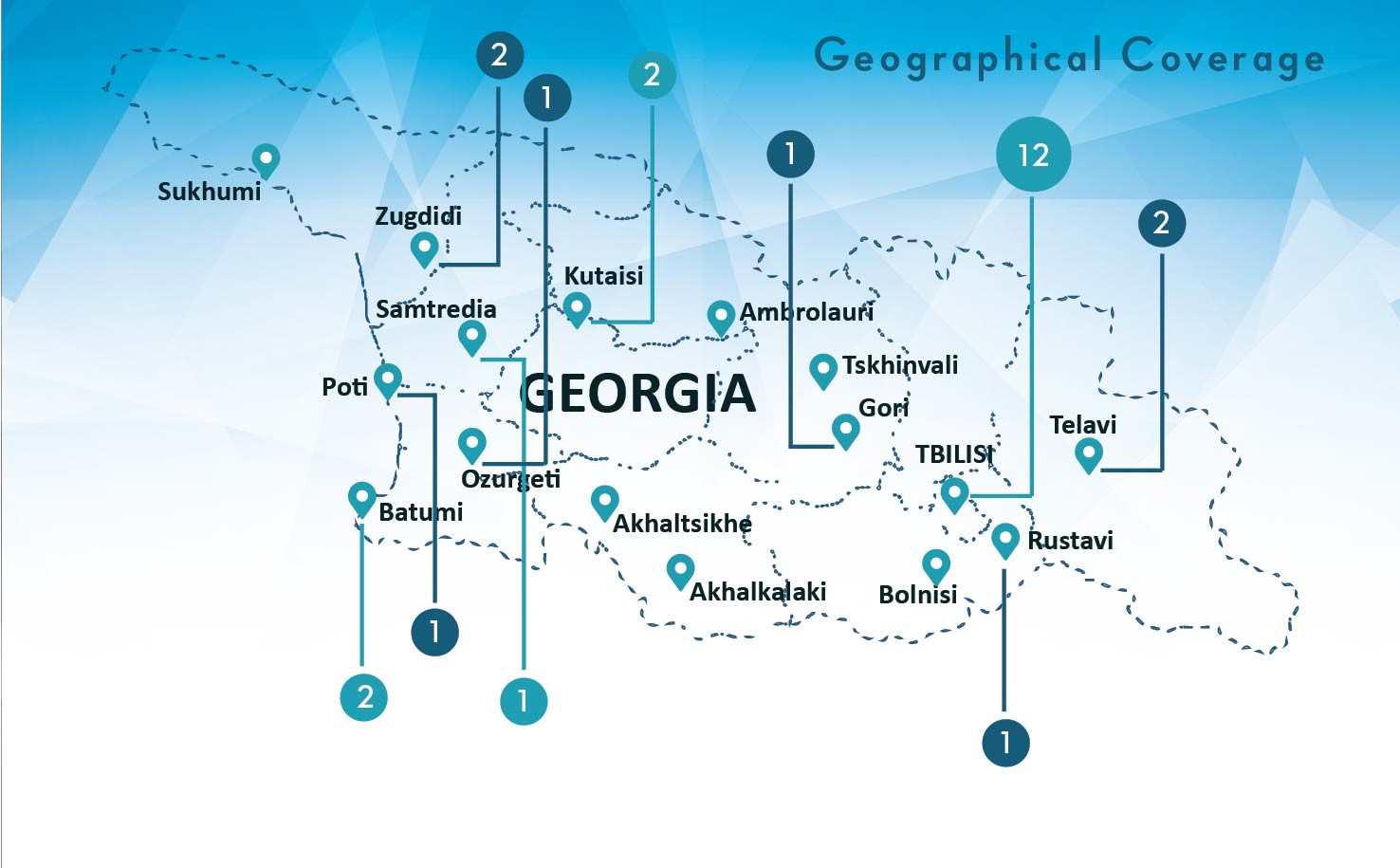

Empowering civil society for engagement in and monitoring the decision making in health sector in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation presented BBS and PSE study findings at the Civil Society Forum

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

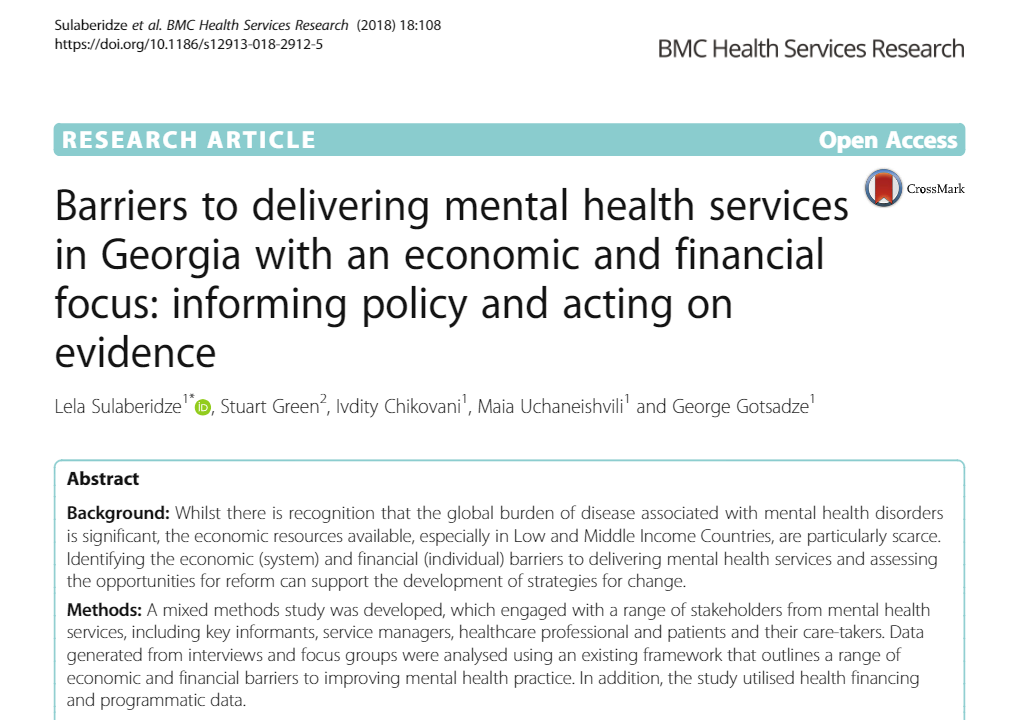

Article: Barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia with an economic and financial focus: informing policy and acting on evidence

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The Interview on population size and Human Immunodeficiency Virus risk behaviors of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

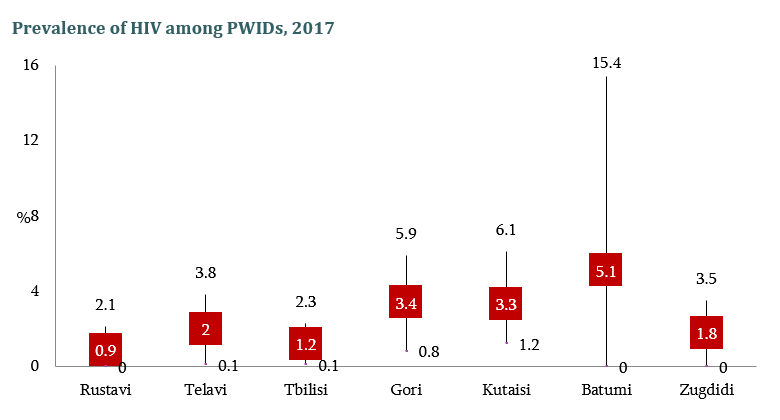

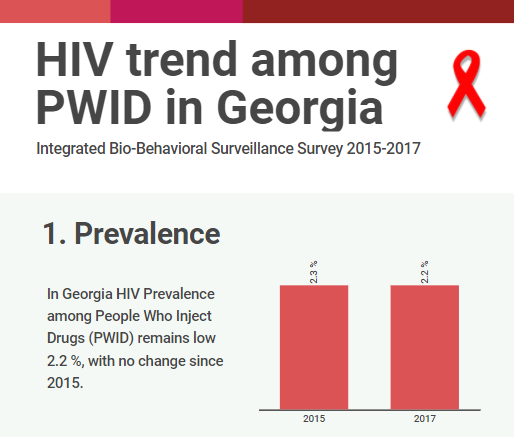

HIV risk and prevention behaviors among People Who Inject Drugs in seven cities of Georgia, 2017

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Conference paper: The Study of Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment among Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients in Georgia to Inform Policy Decision

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

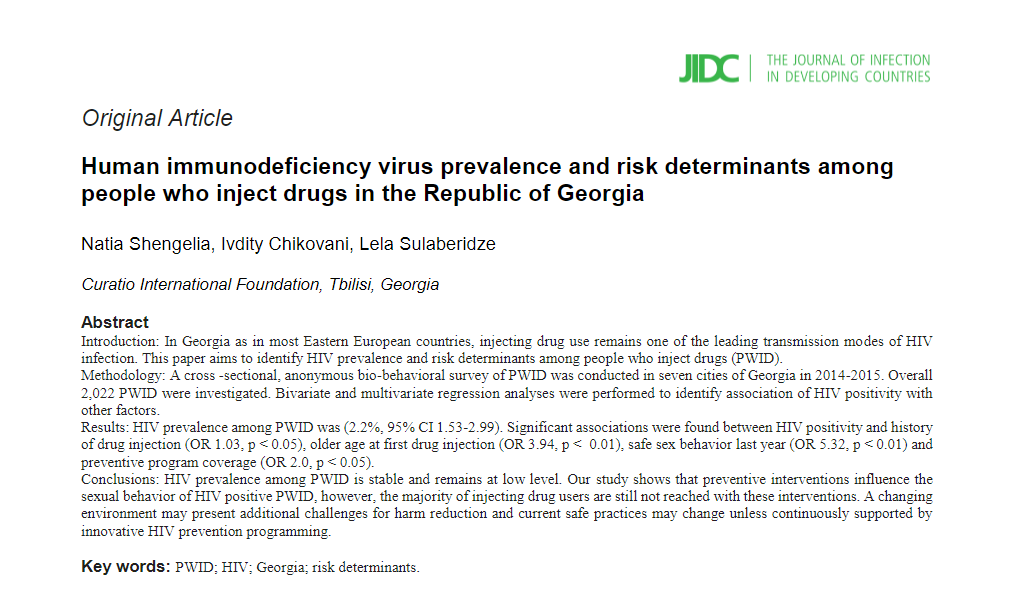

Article: Human immunodeficiency virus prevalence and risk determinants among people who inject drugs in the Republic of Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

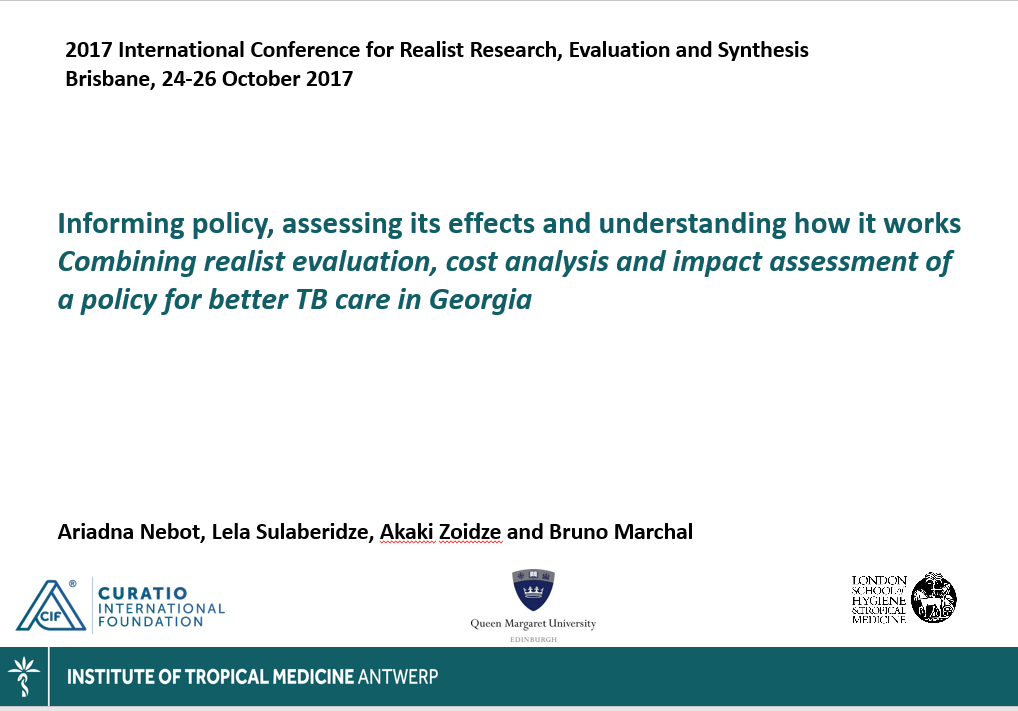

Conference paper about realist evaluation: Informing policy, assessing its effects and understanding how it works for improved Tuberculosis management in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgian Healthcare and its Challenges: Healthcare Expert George Gotsadze will host the lecture

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

17 years in Curatio International Foundation: President Ketevan Chkhatarashvili to Leave Organization

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgian Solution for a Post-Soviet TB Program: Can Integration into Primary Health Care Improve TB Care?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Article: Determinants analysis of outpatient service utilization in Georgia: can the approach help inform benefit package design?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in Georgia (RBF4TB)

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment Among Drug Resistant TB Patients in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regional Sustainability and Transition Coordination Summit 20-21 October, 2016 Vilnius, Lithuania

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Evaluation of UNICEF’s Contribution in Central and Eastern European Five Countries

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Washington DC hosts workshop Immunization Costing: what have we learned, can we do better?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among Men who have Sex with Men in two major cities of Georgia, 2015

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

EPIC Studies – Governments Finance, On Average, More Than 50 Percent Of Immunization Expenses, 2010–11

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among People Who Inject Drugs in 7 cities of Georgia, 2015

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

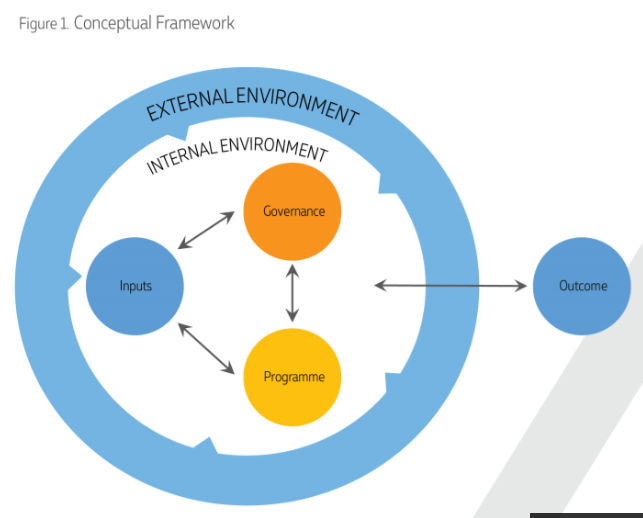

What can be done to improve treatment adherence among tuberculosis patients in Georgia: Looking through health systems lens

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

BioBehavior Surveillance Survey results were represented to the members of Parliament of Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF study results on 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The drivers of facility-based immunization performance and costs. An application to Moldova

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Costs of routine immunization services in Moldova: Findings of a facility-based costing study

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Analyses of Costs and Financing of the Routine Immunization Program and New Vaccine Introduction in the Republic of Moldova

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Health Service Utilization for Mental, Behavioural and Emotional Problems among Conflict-Affected Population in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures for Chronic and Acute Conditions in Georgia: Does benefit package design matter?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation Hosts Health Systems Global Secretariat in Tbilisi, Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

An Impact Evaluation of Medical Insurance for Poor in Georgia: Preliminary Results and Policy Implications

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Georgian Healthcare System Barometer: Experts’ Evaluations of Changes Taking Place in the Healthcare

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The Forbes and Skoll World Forum to discuss HIV/AIDS Epidemic with Director of CIF

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Article on Springer-Determinants of Risky Sexual Behavior Among Injecting Drug Users in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Tobacco Use and Nicotine Dependence among Conflict-Affected Men in the Republic of Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among key populations- Study Findings Published

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation Among Grant Management Solutions Awarded Partners

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Curatio International Foundation revealed the winner of its annual scholarship program

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Impact of global HIV/AIDS initiatives on health systems in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Submission of Applications for CIF Scholarship for Master Program Students near to deadline

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Presentation of the findings of Assessment of Complex Non-Communicable Condition in Low Income Countries

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Contributing to publishing the paper: Circus monkeys or change agents? Civil society advocacy for HIV/AIDS in adverse policy environments

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

National Center for Biotechnology Information published CIF’s scientific paper on Unsafe injection and sexual risk behavior among injecting drug users in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF Study Published in BMC Magazine, The Role of Supportive Supervision on Immunization Program Outcome- a randomized filed trial from Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Releasing results of Bio-behavioral surveillance survey among men having sex with men

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Prices, Availability and Affordability of Medicines in Georgia-the New Study Report Endorsed

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

National and subnational HIV/AIDS coordination: are global health initiatives closing the gap between intent and practice?

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Internship at Curatio International Foundation is challenging for John Hopkins University Students

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF will Launch Fellowship for the Best Student of Healthcare/Public Health Management Faculty

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CoReform Project and the Ministry of Health Mark the Completion of the First Stage of Trainings on ICPC2 Application

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

First Stage of Training Course on Evidence Informed Policy Formulation Crowned

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The Study on System-wide Effects of the Global Fund on Georgia’s Health Care Systems posted on GHIN website

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The research article on Household Catastrophic Health Expenditure-evidence from Georgia and its policy implications published in BMC Health Services Research

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF Hosts workshop on Classifications for Hospital and Laboratory intervention

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF conducted a workshop to discuss HIV/AIDS Surveillance System Assessment results

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF conducted a workshop in the framework of the project funded by the Global Fund

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

The Global Fund Contracted Curatio International Foundation for Consulting Services

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

CIF and MoLHSA conduct a workshop on Integrated Model and Strategic Plan for the Health Information system development in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Dr. George Gotsadze – CIF director and PATH board member presented “Hope for health in a weakened nation”

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Natia Rukhadze – CIF Researcher at the Global HIV/AIDS Initiatives Network (GHIN) international workshop in Dublin, Ireland

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Yale University Announced Selection of Leading Georgian Public Health Expert, Ketevan Chkhatarashvili, as a 2007 Yale World Fellow Yale University announced the selection of the leading Georgian health policy advisor, Ketevan Chkhatarashvili, the preside

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.

Final Report on Family Planning and Reproductive Health Assessment in Georgia

Lapses in education and deregulation may, at least partly, explain the frequency of medical errors, suggests Giorgi Gotsadze, the president of the Curatio International Foundation, a healthcare think-tank based in Tbilisi.