#COVID19 – Evidence and Policymaking: Personal Reflections from an LMIC Setting

by George Gotsadze, President of Curatio International Foundation

and Executive Director of Health Systems Global

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers. Governments are forced to balance policy choices between minimizing the death toll caused by the infection while reducing the negative economic impact expected in the aftermath of the COVID19 outbreak, when hard-hit economies with rising unemployment are expected to leave millions of households without subsistence income.

By now, most of us realize that post-COVID-19 times will come at a significant societal and economic cost, slowing the pace of global development for some years to come. Wealthy nations, at least, are announcing hefty economic packages, supporting middle and low-income families and responding to the economic downturn. Poor countries, meanwhile, are left to choose between: (a) using social distancing to delay the epidemic spike and reduce its magnitude, thereby allowing weak health systems to cater to their patients; and (b) deciding on the length of the “lock-down”, which curtails economic activity for a significant length of time but is highly detrimental to many people living on subsistence, or even average, incomes. Such decisions demand evidence about the virus and its epidemiological characteristics, modeling results estimating the burden on the health system and the economic cost arising from social distancing, information about health systems capacity and available human resources, etc.

The policymaking process in my own country revealed numerous shortcomings in the available evidence, but it also opened up promising and welcoming developments. I decided to reflect on these experiences to reveal the developments, challenges, and possible knowledge gaps that need to be filled:

- Firstly, disease models are essential when dealing with an epidemic of such magnitude. They help to estimate (with a significant degree of uncertainty) the growth of infection spread and the possible burden on the health system – a critical element for health sector preparedness planning. While a search on Google Scholar using the “Epidemic AND Modelling AND LMIC” search term, which was constrained to the last decade, produced 4,130 [1] search results, we were only able to locate a single user-friendly Excel-based modeling tool developed by US CDC FluSurge2.0 for seasonal flu. This was the only tool in the public domain, but it was not suitable for COVID19 estimates. Thus, if you live in an LMIC setting not surrounded by experienced disease modelers (which I assume is the case in many similar settings), you are most likely left without any support. In the current, interconnected world, it should not be allowed for valuable weeks to be lost when drawing up hospital and health sector preparedness plans, especially when hundreds of millions are spent on the disease modeling globally. The Penn Medicine – COVID-19 Hospital Impact Model for Epidemics emerged during the week of March 15th, and thanks to our colleagues around the world, user-friendly modeling tools were developed swiftly and placed online in free public space legally within the subsequent two weeks. I think that in the future, research funders should mandate modelers not only to publish their papers but to also make the models publicly accessible if the world has to prepare for the next pandemic in the Global North and South alike.

- Secondly, it seems there is a significant gap around the impact of non-medical interventions for epidemic control. Most questions asked by policymakers about the impact of social distancing measures on transmission spread and economic costs were hard to answer due to largely patchy evidence. It seems this is an area for future research, not only in high-income settings. It is also important for systematic reviews to support answering such questions when asked in the future.

- Thirdly, close to 390 published papers and pre-prints emerged during the month of March 2020 alone (based on our search). New evidence is being produced almost daily, conveying the “fresh” and essential information needed for preparedness planning and for learning from different country experiences (good and bad alike), etc. Thanks to all those making pre-publications available freely online. Nobody should underestimate the value of this public good, especially in settings similar to ours. While these papers were not peer-reviewed, the benefits probably outweigh the shortcomings, especially when the papers are disseminated through social media and peers render immediate reactions revealing the strength and weaknesses of the studies in question. Looking at peer comments on social media, which was extremely helpful, I was left wondering whether global health journals should consider using artificial intelligence to capture these comments for re-imagined and accelerated peer-review process? It may take time, but if this were possible, it could accelerate the publication of quality and peer-reviewed papers and could be hugely beneficial for the scientific field.

- Finally, the challenges of evidence search revealed the value of global networking, especially for those operating online. We were lucky, as part of Health Systems Global as well as other networks that allowed us to call for help (using appropriate social media and other communication channels), which came without delay. It was great to observe the value of peer support with suggestions, offering online help when faced with technical or other challenges, referring to great websites and repositories, etc. However, I wondered how many of our peers who work on knowledge production-translation are aware of or are able to mobilize such peer support at short notice? All of this led me to the desirability of collecting personal stories around the world about the peer-support channels one could tap into when conducting rapid evidence review. Such stories could help to develop a knowledge product – guidance document benefitting many around the world and enhancing our collective ability to support knowledge to policy links.

To conclude, I am sure that COVID-19 will be over, and that we will learn to live with it after paying a high cost as a society. We will return to “new normal” lives with new lessons and with new opportunities to explore. Of course, this is far from being a full account of our experiences, and I hope to have more time in the future to better reflect on policymaking and evidence needs, knowledge gaps, and emerging opportunities. But it is time to stop here and wish you all good health in this COVID-19-challenged world.

[1] Search carried on March 30th, 2020

Latest News

Integrated Bio-behavioral surveillance and population size estimation survey among Female Sex Workers in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia, in 2024

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation at Eighth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2024)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

“The Informatics and Data Science for Public Health: Sustainment Plan for Skilled Labor Force Development”

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Janina Stauke from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine shares her internship experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Jolly Mae Catalan fromUniversité Libre de Bruxelles shares her internship experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgia’s Journey to Integrating Rehabilitation Services into the Health System: Insights and Lessons

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Report on Rehabilitation Data Flow in Georgia’s Health Information System

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgia: a primary health care case study in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Adult vaccination in Asia and the Pacific

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Assessment of the Quality of Maternal and Neonatal Services in Montenegro

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Barometer Study: Pharmaceutical Sector in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian state rehabilitation program: implementation research study report

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

NEW Barometer, study focusing on the pharmaceutical sector

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Linked’s workshop on HPV vaccine introduction and scale up, held on July 11-12th, 2023

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Training program focusing on interdisciplinary evaluation of rehabilitation interventions and patient outcomes

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Unlocking Success Through Learning: Workshop on Strengthening HR Capacity and Performance Management in Immunization

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence and fostering civic engagement

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF and the Results for Development / Accelerator combined their expertise to co-author an insightful blog, shedding light on Georgia’s commendable efforts to overcome limited data challenges and develop evidence-based policies for financing rehabilitation services

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Culminating event – Building Institutional Capacity for Health Policy and Systems Research and Delivery science (BIRD) in six WHO Regions

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Report on Phased (Stepwise) Plan for the Capability Development of the Priority Rehabilitation Services

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Report on prioritization of rehabilitation services in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Report on Rehabilitation Service Costing and Budgeting

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Mental health of young people during the COVID-19 pandemic

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Promote evidence-based policies in the pharmaceutical sector by generating evidence

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Mandatory Vaccination and Green Passes – Review of International Experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Sustaining Public Health Gains after Donor Transition: What can we learn about Georgia?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation at Seventh Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2022)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation at Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

EECA HIV Sustainability Summit 2022 in Tbilisi

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Study report: Adaptations made in TB response during Covid-19 pandemic in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

New review of our recent study on Immunization in Kazakhstan

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

New case study: Sustaining effective coverage with Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) in Georgia in the context of transition from external assistance

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

New case study: National Immunisation Program Transition from external assistance

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

“Strengthening Health Systems for Accessible Rehabilitation Services in Georgia” – Workshop

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Strengthening the Delivery of Immunisation Services Through PHC Platforms-Workshop

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

New Article published in the journal Frontiers in Public Health

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

New Paper: A transdiagnostic psychosocial prevention-intervention service for young people in the Republic of Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Vaccine Procurement and Supply for the Expanded Program of Immunization in Kazakhstan

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd) – Workshop

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Workshop to discuss the risk assessment of future TB migrants

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar : Matters of Scale and Integration in Digital Health Ecosystems

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Data Analysis and Synthesis Workshop – analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

External Reference Pricing Policy: A Possible Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Policy in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Rapid reviews of health policy and systems evidence

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Paper: Soviet legacy is still pervasive in health policy and systems research in the post-Soviet states

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Strategic Fellowship – series of training courses for students

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian NIP faces challenges in sustaining the outcomes achieved

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Enroll to the CIF’s Strategic Fellowship Programme

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Article: How do participatory methods shape policy? Applying a realist approach to the formulation of a new tuberculosis policy in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Bundled Payment Methods: An Alternative Payment Method to Contain Healthcare Costs in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

HOW TO MAINTAIN ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION DURING COVID-19? EXPERIENCES FROM ARMENIA, GEORGIA, AND UZBEKISTAN

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

DRUG CHECKING: An Essential Response to Emerging Harm Reduction Needs

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

GEORGIA COVID-19 VACCINE COMMUNICATIONS CAMPAIGN TO ADDRESS HESITANCY ISSUES

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Supporting Evidence-Informed Policy making and Action in Six WHO Regions

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian Healthcare Barometer XIV Wave The analysis of financial stability and risks in healthcare

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Call for educational Strategic Policy Fellowship Program

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

We are pleased to announce that The Sixth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR2020) has opened

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Discussing interim results of research project: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia (PAMAd)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Effects of Pay for Performance on utilization and quality of care among Primary Health Care providers in Middle and High-Income countries

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Does pay for performance work to improve immunization coverage?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CAN SOCIAL MEDIA MONITORING LEAD TO IMPROVED PERCEPTIONS ABOUT IMMUNIZATION?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The first phase of the joint fellowship program of the Curatio International Foundation and the Knowledge to Policy Center (K2P) at the American University of Beirut has been successfully implemented

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT WEBINAR: Incremental Costs of Routine Immunization, Campaigns, and Outreach Services During COVID-19

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Webinar: Assessing Bottlenecks to Adequate and Predictable Vaccine Financing

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT WEBINAR: Designing Behavioural Strategies for Immunization in a Covid-19 Context

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Concentration and fragmentation: analyzing the implications of the structure of Georgia’s private healthcare market for quality and accessibility (ConFrag)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Discussion Group: COVID-19 Impact on Immunization Programs

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The COVID-19 epidemic in Georgia Projections and Policy Options

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Modeling of Four Possible Scenarios of COVID-19 epidemics in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Application for Summer Internship program is closed

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Webinar: Key Considerations for Integrating Immunization with Other Primary Health Care Services

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgia Sharing knowledge to Armenia to strengthen immunization legislation

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Call for Interns as researchers is now open

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Improving access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Webinar: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy Challenges

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Project on “Technical Assistance Using Modern Technology for TB Prevention, Diagnosis, and Increased Quality Treatment” was closed

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Dialogue on Pharmaceutical pricing policies to improve the population’s access to pharmaceuticals in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Webinar: Implementing a High Performing Immunization Program within the Context of National Health Insurance: What can we Learn from Thailand?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

LNCT Webinar: Strengthening Public-Private Engagement for Immunization Delivery

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Implementing new research: Prevention of Addiction and Mental Health in Adolescents in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgia’s introduction of the Hexavalent vaccine: Lessons on successful procurement and advocacy

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgia Primary Health Care Profile: 6 Year after UHC program introduction

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

National consultations to propose a new model of TB funding

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

HSR2020: RE-IMAGINING HEALTH SYSTEMS FOR BETTER HEALTH AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CALL FOR MENTEES: PUBLICATION MENTORSHIP FOR FIRST-TIME WOMEN AUTHORS IN THE FIELD OF HPSR

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

A pilot of a new intervention launched to Improve adherence to TB treatment and its outcomes in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Training for epidemiologists and health workers on TB contact tracing new guideline

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Workshop on using modern technology for TB prevention, diagnosis and increased quality treatment

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

K2P Mentorship Program on Building Institutional Capacity on Evidence Informed Policy Making

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Training on using Research Evidence for Policy Making

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Doing embedded development and research – reflections on the start of the Results4TB programme

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Healthcare Advocacy Coalition (HAC) for Human Oriented Healthcare

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Introductory Meeting on the project ‘Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Policy-Making’

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Taavy Miller from University of North Carolina shares her internship experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Building Institutional Capacity for HPSR and Delivery Science- CIF is Europe region HUB

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Inter-regional workshop in preparation for transitioning towards domestic financing in TB, HIV and Malaria programmes

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Memorandum of Cooperation between the Health and Social Issues Committee of the Parliament of Georgia and Curatio International Foundation

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Embedding Rapid Reviews in Health Systems Decision-Making (ERA)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation at the Global Symposium on Health Systems Research

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The civil society gathered for the fourth time to discuss healthcare system challenges in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Project: HIV risk behavior among Men who have Sex with Men – Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey and Population Size Estimation

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation at AIDS2018

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Big Pharma Greed and Artificial Prices – Knocking on Door to Limit Access to HIV Medicines in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Civil society is gathering for the third time to hold a discussion about the healthcare

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar: Gavi Vaccine Prices Post-Transition

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar: Mapping and consensus of global competencies set for the field of HPSR: A progress update and HSG round table discussion

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Health Systems Global Publishes Annual Report 2017

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar: Vaccine Forecasting and Budgeting Tools and Best Practices

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Technical Assistance for evaluation of transition readiness and preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for Global Fund-supported programs in Tajikistan

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Technical Assistance for the preparation of Transition and Sustainability Plan for HIV program in Philippines

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Discussing the accessibility of medicines in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar: Integrating gender into health system strengthening in conflict and crisis-affected settings; what’s in our toolkit?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Article: Barriers to mental health care utilization among internally displaced persons in the republic of Georgia: a rapid appraisal study

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Why Georgians second-guess their doctors – Deregulation has left Georgian medical care something many Georgians would rather avoid

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Ara Srinagesh from New York University Shares her Internship Experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar on The peer review process – what happens when you send your manuscript to a journal

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Webinar on Improving Quality of Care during Childbirth: Learnings and Next Steps from the BetterBirth Trial

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Civil Society is Being United to Discuss Healthcare System Issues

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation for a TB-Free World

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Summer Internship Program is now open

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Closing Project: Tuberculosis Community Systems Strengthening in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Primary Health Care Systems: Georgia case study

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

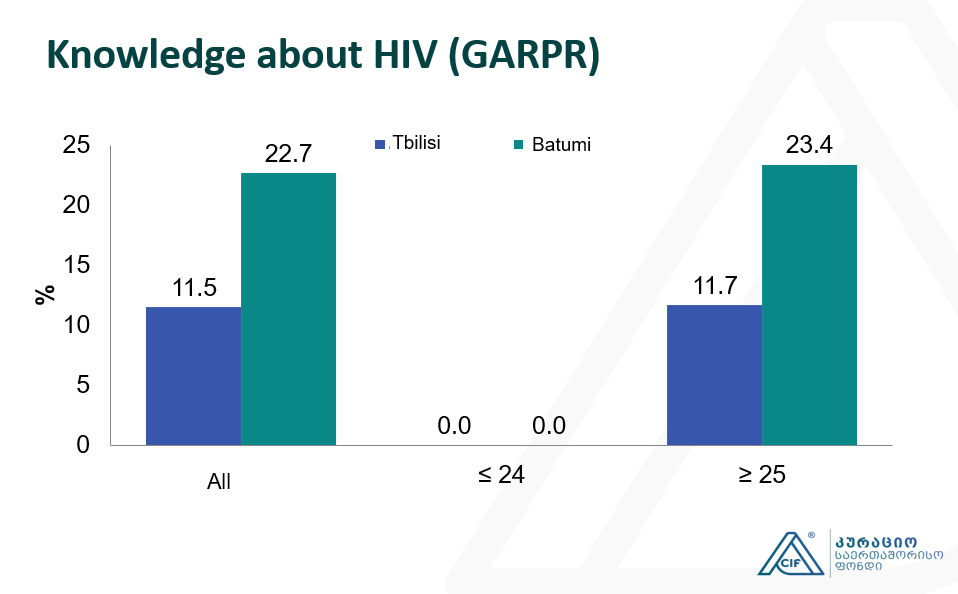

Integrated Bio-behavioral surveillance and population size estimation survey among Female Sex Workers in Tbilisi and Batumi, Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Applying a Health Policy and Systems Research lens to Human Resources for Health: Capacity building, leadership and politics

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF hosts Aradhana Srinagesh throughout the winter internship program

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

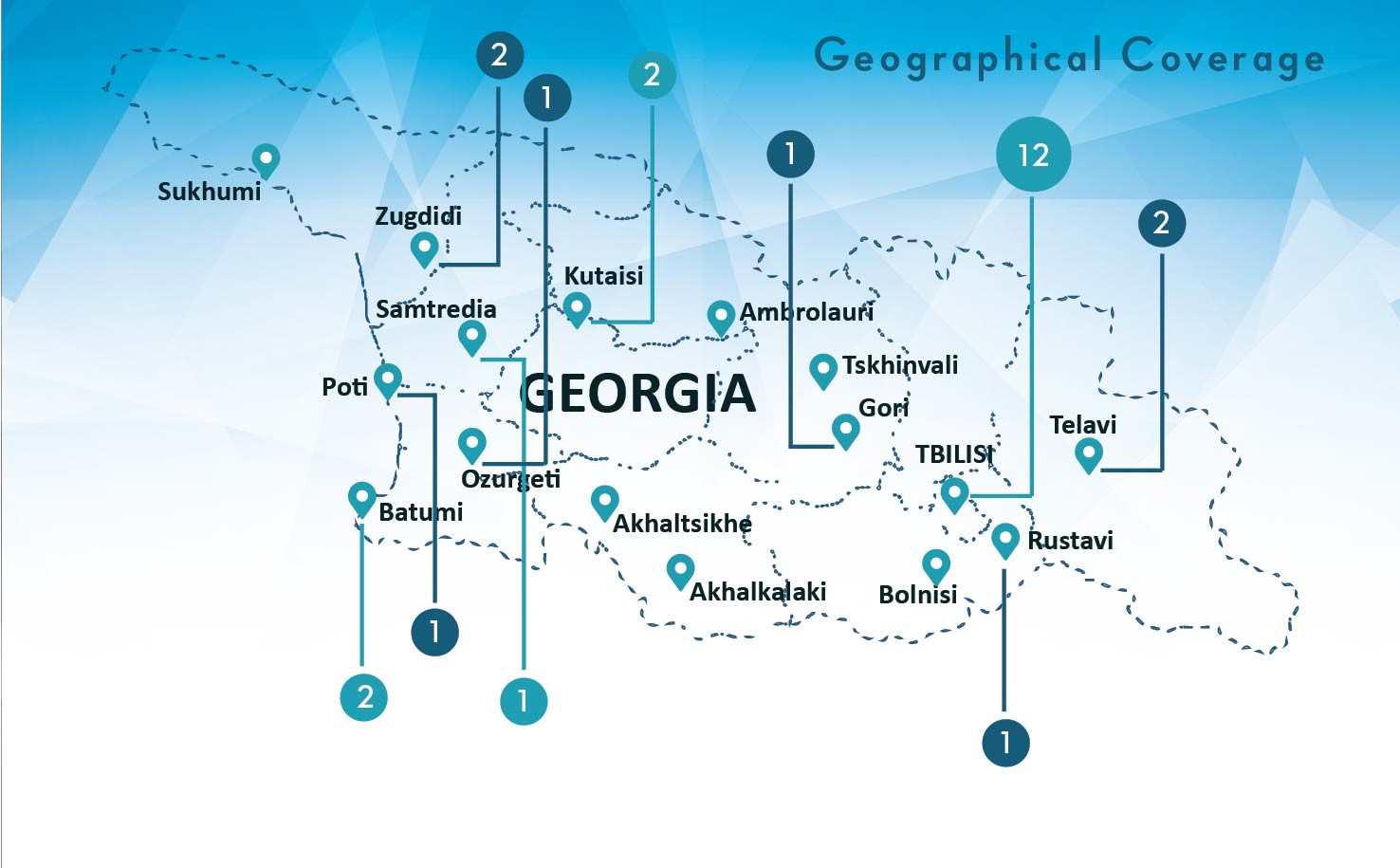

Empowering civil society for engagement in and monitoring the decision making in health sector in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation presented BBS and PSE study findings at the Civil Society Forum

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

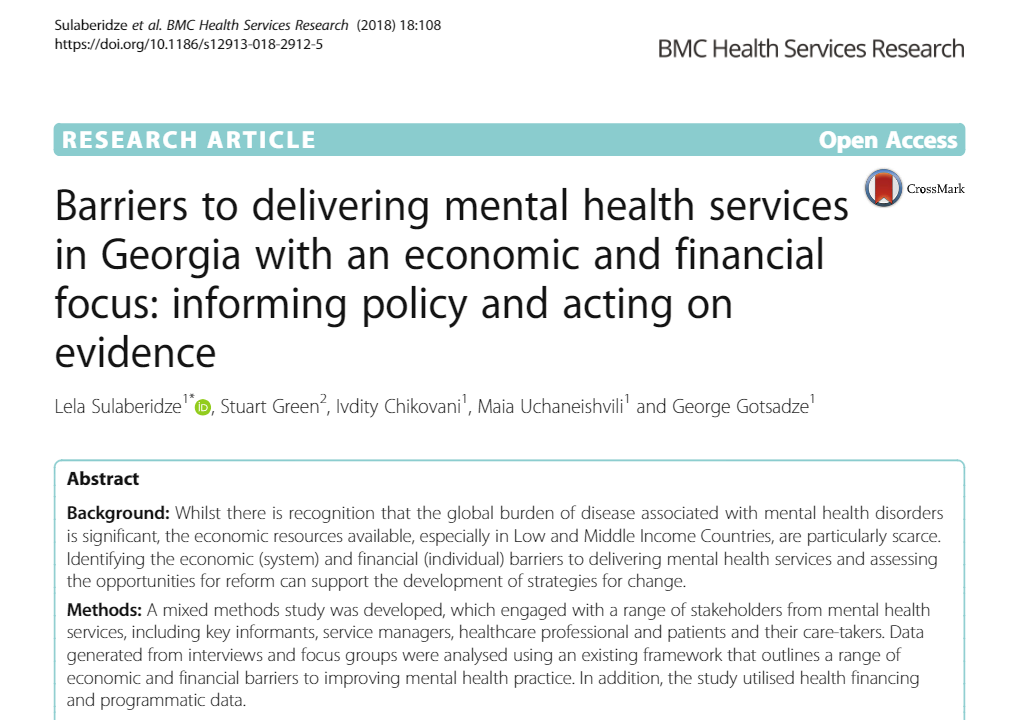

Article: Barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia with an economic and financial focus: informing policy and acting on evidence

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The Interview on population size and Human Immunodeficiency Virus risk behaviors of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Population Size Estimation of People who Inject Drugs in Georgia 2016-2017

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

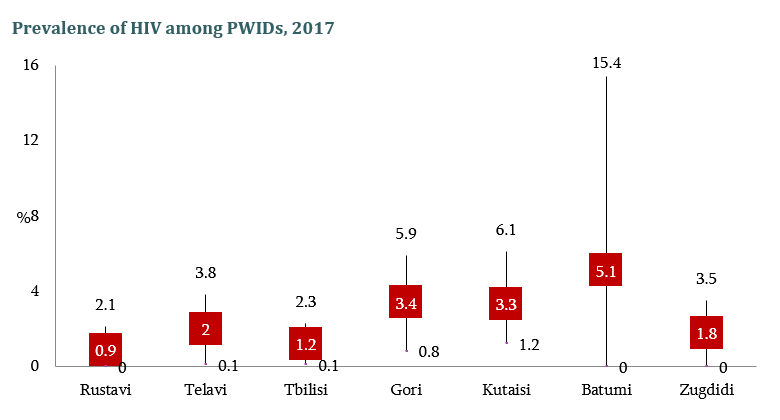

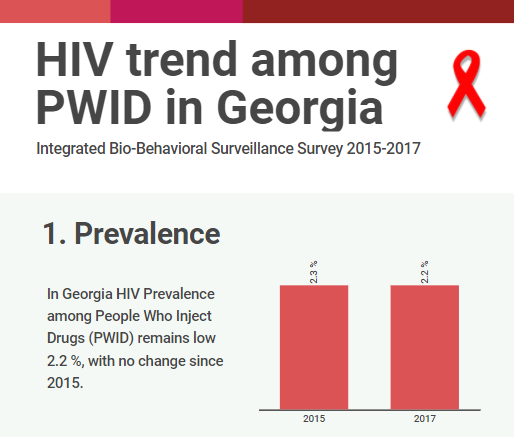

HIV risk and prevention behaviors among People Who Inject Drugs in seven cities of Georgia, 2017

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Conference paper: The Study of Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment among Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients in Georgia to Inform Policy Decision

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

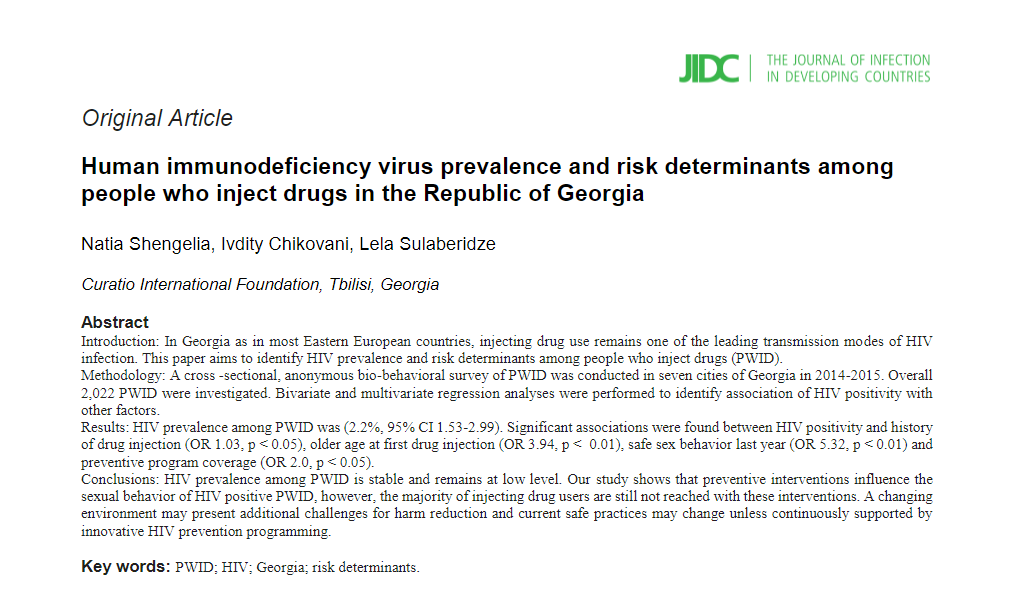

Article: Human immunodeficiency virus prevalence and risk determinants among people who inject drugs in the Republic of Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Conference paper about realist evaluation: Informing policy, assessing its effects and understanding how it works for improved Tuberculosis management in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian Healthcare and its Challenges: Healthcare Expert George Gotsadze will host the lecture

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

17 years in Curatio International Foundation: President Ketevan Chkhatarashvili to Leave Organization

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Be ready for the Best Internship Experience

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Apply for Our Winter Internship Program

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian Solution for a Post-Soviet TB Program: Can Integration into Primary Health Care Improve TB Care?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Moving Forward: Second PT workshop with TB stakeholders in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Article: Determinants analysis of outpatient service utilization in Georgia: can the approach help inform benefit package design?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in Georgia (RBF4TB)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Forbes Georgia: The Importance of Evidence in Decision Making

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Barriers and Facilitators to Adherence to Treatment Among Drug Resistant TB Patients in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Summer internship program 2017 is open now!

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

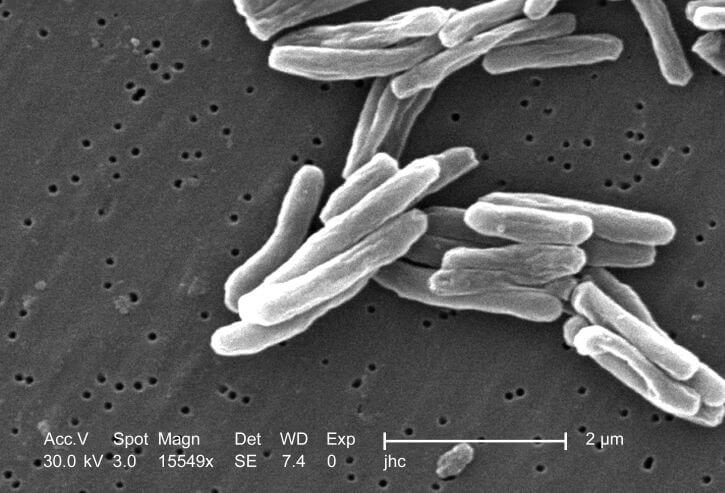

New Study Findings About Tuberculosis

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation: Transition and Sustainability Portfolio

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Article: Privilege and inclusivity in shaping Global Health agendas

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regional Sustainability and Transition Coordination Summit 20-21 October, 2016 Vilnius, Lithuania

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Internship Announcement, Winter 2016-17

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Evaluation of UNICEF’s Contribution in Central and Eastern European Five Countries

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF researchers represented on Global Conference AIDS2016

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

UHC 2030: Building an Alliance to Strengthen Health Systems

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Pharmaceutical Price and Availability Study (Fifth Wave Results)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Assessment of GAVI Alliance HSS support to Tajikistan

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Final Evaluation of Gavi’s Support to Albania

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

HIV risk and prevention behaviours among Prison Inmates in Georgia, 2015

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Washington DC hosts workshop Immunization Costing: what have we learned, can we do better?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among Men who have Sex with Men in two major cities of Georgia, 2015

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

EPIC Studies – Governments Finance, On Average, More Than 50 Percent Of Immunization Expenses, 2010–11

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey among People Who Inject Drugs in 7 cities of Georgia, 2015

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

TB Community Systems Strengthening in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

What can be done to improve treatment adherence among tuberculosis patients in Georgia: Looking through health systems lens

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

BioBehavior Surveillance Survey results were represented to the members of Parliament of Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Announcing Winter Internship Program 2016

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Regional High Level Dialogue ‘Road to Success’, Tbilisi, Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF study results on 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Response to the “Final evaluation of GAVI support to Bosnia and Herzegovina”

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The drivers of facility-based immunization performance and costs. An application to Moldova

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Awaiting the results of Prisoners’ Behavior Surveillance Survey (BSS)

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Costs of routine immunization services in Moldova: Findings of a facility-based costing study

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Analyses of Costs and Financing of the Routine Immunization Program and New Vaccine Introduction in the Republic of Moldova

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Health Service Utilization for Mental, Behavioural and Emotional Problems among Conflict-Affected Population in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures for Chronic and Acute Conditions in Georgia: Does benefit package design matter?

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation Hosts Health Systems Global Secretariat in Tbilisi, Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

An Impact Evaluation of Medical Insurance for Poor in Georgia: Preliminary Results and Policy Implications

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Policy Information Platform (PIP) Expert Consultation Meeting

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Civil Society Forum organized by Country Coordination Mechanism

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Drexel University on CIF Internship Program

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Publishes the Short Movie on 20 Years of Healthcare, 2014

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Publishes Anniversary Publication ’20 Years of Health Care, 2014

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Celebrated the 20th Anniversary

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Georgian Healthcare System Barometer: Experts’ Evaluations of Changes Taking Place in the Healthcare

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

BlogTalkRadio to Host CIF President

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Winner of CIF Students Fellowship Program for 2013-2014

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Mental Health Among IDPs in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

The Forbes and Skoll World Forum to discuss HIV/AIDS Epidemic with Director of CIF

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Participation in the Private Sector in Health Symposium 2013

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Article on Springer-Determinants of Risky Sexual Behavior Among Injecting Drug Users in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Tobacco Use and Nicotine Dependence among Conflict-Affected Men in the Republic of Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among key populations- Study Findings Published

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Think Tanks Signed an Ethical and Quality Standards Document

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Hosting interns from international universities

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Hosting interns from international universities

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF’s contribution to Investing in Global Health and Development

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Assessing the Health Insurance for the Poor in Georgia

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation Among Grant Management Solutions Awarded Partners

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Fourth Wave Results of Pharmaceutical Study Published

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

CIF Calls for participation in internship program for 2012-2013

As I embark on writing this blog, the global outbreak of COVID-19 is posing a growing threat to the health and well-being of our societies. The unfolding global health and economic crisis demands bold actions from all of us, but most importantly from policymakers.

Curatio International Foundation revealed the winner of its annual scholarship program